Preface

The Open Group

The Open Group is a global consortium that enables the achievement of business objectives through technology standards. With more than 870 member organizations, we have a diverse membership that spans all sectors of the technology community – customers, systems and solutions suppliers, tool vendors, integrators and consultants, as well as academics and researchers.

The mission of The Open Group is to drive the creation of Boundaryless Information Flow™ achieved by:

- Working with customers to capture, understand, and address current and emerging requirements, establish policies, and share best practices

- Working with suppliers, consortia, and standards bodies to develop consensus and facilitate interoperability, to evolve and integrate specifications and open source technologies

- Offering a comprehensive set of services to enhance the operational efficiency of consortia

- Developing and operating the industry’s premier certification service and encouraging procurement of certified products

Further information on The Open Group is available at www.opengroup.org.

The Open Group publishes a wide range of technical documentation, most of which is focused on development of Standards and Guides, but which also includes white papers, technical studies, certification and testing documentation, and business titles. Full details and a catalog are available at www.opengroup.org/library.

The TOGAF® Standard, a Standard of The Open Group

The TOGAF Standard is a proven enterprise methodology and framework used by the world’s leading organizations to improve business efficiency.

This Document

This document is a TOGAF® Series Guide to Architecture Project Management. It has been developed and approved by The Open Group.

The document supersedes Architecture Project Management, White Paper (W16B), August 2016, published by The Open Group.

More information is available, along with a number of tools, guides, and other resources, at www.opengroup.org/architecture.

About the TOGAF® Series Guides

The TOGAF® Series Guides contain guidance on how to use the TOGAF Standard and how to adapt it to fulfill specific needs.

The TOGAF® Series Guides are expected to be the most rapidly developing part of the TOGAF Standard and are positioned as the guidance part of the standard. While the TOGAF Fundamental Content is expected to be long-lived and stable, guidance on the use of the TOGAF Standard can be industry, architectural style, purpose, and problem-specific. For example, the stakeholders, concerns, views, and supporting models required to support the transformation of an extended enterprise may be significantly different than those used to support the transition of an in-house IT environment to the cloud; both will use the Architecture Development Method (ADM), start with an Architecture Vision, and develop a Target Architecture on the way to an Implementation and Migration Plan. The TOGAF Fundamental Content remains the essential scaffolding across industry, domain, and style.

Trademarks

ArchiMate, DirecNet, Making Standards Work, Open O logo, Open O and Check Certification logo, Platform 3.0, The Open Group, TOGAF, UNIX, UNIXWARE, and the Open Brand X logo are registered trademarks and Boundaryless Information Flow, Build with Integrity Buy with Confidence, Commercial Aviation Reference Architecture, Dependability Through Assuredness, Digital Practitioner Body of Knowledge, DPBoK, EMMM, FACE, the FACE logo, FHIM Profile Builder, the FHIM logo, FPB, Future Airborne Capability Environment, IT4IT, the IT4IT logo, O-AA, O-DEF, O-HERA, O-PAS, Open Agile Architecture, Open FAIR, Open Footprint, Open Process Automation, Open Subsurface Data Universe, Open Trusted Technology Provider, OSDU, Sensor Integration Simplified, SOSA, and the SOSA logo are trademarks of The Open Group.

Excel and MS Project are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries.

PMBOK is a registered trademark of the Project Management Institute, Inc. which is registered in the United States and other nations.

PRINCE2 is a registered trademark of AXELOS Limited.

All other brands, company, and product names are used for identification purposes only and may be trademarks that are the sole property of their respective owners.

About the Authors

The authors of this Guide have backgrounds in both Enterprise Architecture and Project Management.

(Please note affiliations were current at the time of approval.)

Jacek Presz

Jacek Presz (http://linkedin.com/in/jacekpresz) is an experienced Enterprise Architect focused on planning and supporting technology-enabled business transformation. He has held Chief Enterprise Architect positions in Banking, Technology, and Power & Utilities companies. While working for one of the leading consulting firms, he delivered Architecture Projects on a strategic and segment level for clients in different sectors. He is actively engaged in TOGAF® Standard development.

Łukasz Wrześniewski, The Open Group Invited Expert

Łukasz Wrześniewski (http://linkedin.com/in/lukaszwrzesniewski) works as an Agile Transformation and Enterprise Architecture Consultant. He specializes in Agile Enterprise Architecture and Agile Program Management. He is also an active trainer who provides TOGAF®, ArchiMate®, IT4IT™, and Scaled Agile training courses. He is participating in the Agile Enterprise Architecture team and in the Architecture, IT4IT, ArchiMate Harmonization Project as an invited expert.

Łukasz Drążek, PMP

Łukasz Drążek, PMP (http://linkedin.com/in/lukaszdrazek) is a manager with experience in largescale IT projects for the banking, public, energy, power & utilities, and FMCG sectors. He specializes in project and program management, program recovery, technology-enabled transformation, and change management. He is responsible for the IT Delivery Management practice in the Digital & Technology Enablement Advisory Group, EY Poland.

Maciej Iwaniuk, PMP

Maciej Iwaniuk, PMP (http://linkedin.com/in/maciekiwaniuk) is a certified Project Manager and experienced Project Auditor with experience in local and international project planning, execution, and management. He is involved in Project Management method design, development, and implementation. He is an Integration Leader at EY EMEIA Advisory Center.

Bartłomiej Rafał, EY

Bartłomiej Rafał (http://linkedin.com/in/bartlomiejrafal) is a TOGAF Certified practitioner and a Senior Analyst in the Digital & Technology Enablement Advisory Group, EY Poland. During his career at EY, he has been involved in some of the largest architecture transformation programs for leading organizations around the world. Currently, he is interested in improving his Enterprise Architecture skill set (especially in data and application domains), and applying it to support organizations intending to undergo Digital Transformation.

Filip Szymański, EY

Filip Szymański (http://linkedin.com/in/szymanskifilip) is a TOGAF Certified practitioner and a manager with experience in leading strategic and tactical change management projects focused around Enterprise Architecture. He specializes in designing Enterprise Architecture, as well as information systems architectures aimed at enabling value delivery to the business. He is responsible for the IT Architecture practice in the Digital & Technology Enablement Advisory Group, EY Poland.

Piotr Papros

Piotr Papros (http://linkedin.com/in/papros) is an IT Manager experienced in leading complex IT projects, programs, and services for worldwide institutions. He is a Lean-Agile program consultant, having served as a Lean-Agile coach in transformation efforts at an organization level. He is an enthusiast of gamification, enterprise change management, and sport.

Acknowledgements

The Open Group gratefully acknowledges the authors and also past and present members of The Open Group Architecture Forum for their contribution in the development of this Guide.

The authors would like to thank the following key contributors and reviewers, without whom the original White Paper would not have been possible:

- Atila Belloquim, Gnosis

- Sonia Gonzalez, The Open Group

- Kirk Hansen, Kirk Hansen Consulting

(Please note affiliations were current at the time of approval.)

Referenced Documents

The following documents are referenced in this TOGAF® Series Guide.

(Please note that the links below are good at the time of writing but cannot be guaranteed for the future.)

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 5th Edition, Project Management Institute (PMI), 2013; refer to www.pmi.org

- ArchiMate® 3.1 Specification, a standard of The Open Group (C197), published by The Open Group, November 2019; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/c197

- Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2®, 2009 Edition, AXELOS, 2009

- Practice Standard for Project Risk Management, Project Management Institute (PMI), 2009; refer to www.pmi.org

- The PRINCE2® Foundation Training Manual, Frank Turley, 2013

- The TOGAF® Standard, 10th Edition, a standard of The Open Group (C220), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/c220

- TOGAF® Series Guide: Architecture Skills Framework (G198), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/g198

The following documents are not directly referenced in the text, but may be useful:

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd Edition, Project Management Institute (PMI), 2004

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 4th Edition, Project Management Institute (PMI), 2009

- Understanding PRINCE2®, Ken Bradley, 2002

- Directing Successful Projects with PRINCE2®, AXELOS, 2009

1.1 Overview

Architecture Projects are typically complex in nature. They need proper Project Management to stay on track and deliver on promise. This Guide is intended for people responsible for planning and managing Architecture Projects. We explain how the TOGAF® Architecture Development Method (ADM) can be supplemented with de facto methods and standards such as PRINCE2® or PMBOK® to strengthen Project Management and improve the probability of success for Architecture Projects.

This Guide provides Architecture Project Teams with an overall view and detailed guidance on what processes, tools, and techniques of PRINCE2 or PMBOK can be applied alongside the TOGAF ADM for project planning, monitoring, and control. Further, a detailed mapping of the processes and deliverables of the TOGAF framework against PRINCE2 and PMBOK is provided to visualize how those concepts come together.

This Guide is not intended to serve as a Project Management method guidance book. We explain what Project Management tools and techniques should be applied to Architecture Projects, but we rely on specific PRINCE2 and PMBOK publications for detailing those techniques or tools.

We hope that the introduction of Project Management techniques to Architecture Projects will improve the chances for success of delivered value and solutions in a mature and professional way, supporting The Open Group vision of Boundaryless Information Flow™.

1.2 Background

According to the TOGAF Standard, Enterprise Architecture is the structure of enterprise components, their inter-relationships, and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over time. Enterprise is the highest level of description of an organization and typically covers all missions and functions; it can span multiple organizations.

The TOGAF Standard includes the Architecture Development Method (ADM) that aims to be an industry standard method for developing and implementing an Enterprise Architecture. This method focuses on delivery of architecture products.

In the TOGAF Standard, architecture products are delivered through execution of tasks described in the ADM. These tasks are grouped into inter-related phases, each of which includes a number of steps. Completing an ADM cycle can be a complex task. Therefore, architecture products delivery is often executed as a project.

Architecture Project is not a term defined in the TOGAF Standard; however, it is used often for a project undertaken to define and describe an Enterprise Architecture to be implemented. Therefore, in this Guide, the term “Architecture Project” encompasses all activities undertaken within Phases A to F, and Requirements Management.

Figure 1: Architecture Project Relationship to the TOGAF ADM (Adapted from the TOGAF Standard)

A key result of Phases A to F is an Architecture Definition Document, which describes the Enterprise Architecture to be implemented in Phase G and maintained in Phase H. Therefore, at the end of Phase F the Enterprise Architecture to be implemented is defined and described – and the Architecture Project, by our definition, is completed.

The Preliminary Phase, Phase G, and Phase H are out of scope for the Architecture Project. The Preliminary Phase is concerned with ensuring an Enterprise Architecture capability of the organization. The goal of Phase G is to govern implementation of the Enterprise Architecture. Typically, it is run as a separate endeavor (a project or a set of projects). The goal of Phase H is to maintain the Enterprise Architecture implemented – it is related to operational business (or process) rather than project management.

1.3 Why do we need a Guide on Architecture Project Management?

The TOGAF ADM details objectives, approach, inputs, steps, and outputs of the Enterprise Architecture development phases. However, it is not specific on how to manage an Architecture Project and leaves that to methods that focus on Project Management.[1]

Project Management is the planning, delegating, monitoring, and control of all aspects of the project, and the motivation of those involved, to achieve the project objectives within the expected performance targets for time, cost, quality, scope, benefits, and risks.[2] Market-leading Project Management methods include PRINCE2 and PMBOK. They can be used to enhance an Architecture Project’s chances of success.

Not all TOGAF practitioners are familiar with Project Management methods. Even for those who are, there is no guidance on how to use and align the TOGAF framework with these methods.

The intent of this Guide is to provide guidelines for TOGAF architects on how to manage an Architecture Project. We suggest an approach that supplements the TOGAF ADM with selected Project Management techniques. The goal of this approach is to enhance an Architecture Project’s chances of success through better planning, monitoring, and communication.

1.4 Document Scope and Structure

This Guide is structured in the following sections, with a specific target audience in each case:

- Managing Architecture Projects (Chapter 2) describes a high-level Project Management approach for developing an Enterprise Architecture

The target audience for this section is Enterprise Architects, Project Management professionals, and stakeholders of Architecture Projects who want to understand the key relationships between the TOGAF Standard and Project Management areas.

- Detailed Guidance (Chapter 3) describes a detailed Project Management approach for developing an Enterprise Architecture

It includes a step-by-step guide to Architecture Project initiating, planning, monitoring, and closing. The target audience of this section is Enterprise Architects who are familiar with the TOGAF Standard and who lead Architecture Projects.

- PRINCE2 to ADM Mapping (Chapter 4) and PMBOK to ADM Mapping (Chapter 5) present detailed mappings between the phases of the TOGAF ADM and PRINCE2 and PMBOK processes, respectively

These sections provide a foundation on which the guidance was built and are included for reference.

1.5 Constraints

This Guide explores how Project Management methods can supplement the TOGAF ADM in Architecture Project delivery. It focuses on PRINCE2 and PMBOK as proven practices in the Project Management area.

Agile Project Management methods are out of scope for this Guide. In our experience, the TOGAF framework can be tailored to use an agile approach. Such tailoring can provide important benefits. However, it is not explored in this Guide.

This section describes a general, high-level Project Management approach for developing an Enterprise Architecture. The target audience for this section is Enterprise Architects, Project Management professionals, and stakeholders of Architecture Projects who want to understand the key relationships between the TOGAF Standard and Project Management areas.

2.1 Architecture Project Definition

An Architecture Project is an endeavor undertaken to define and describe the Enterprise Architecture to be implemented. In TOGAF terms, as shown in Figure 1, it encompasses all activities undertaken within the Phases A to F and Requirements Management of the ADM. Practically, it can be a stand-alone project or part of a larger effort (e.g., a program).

|

|

An Architecture Project does not include the Preliminary Phase, Phase G, or Phase H of the ADM. The Preliminary Phase focuses on establishing an Architecture Capability rather than delivery of an Architecture Definition. It can initiate an Architecture Project when necessary (outputs from the Preliminary Phase, especially Request for Architecture Work, are treated as an input to the Architecture Project). Phase G (Implementation Governance) is about implementing the architecture, not defining it. It can be a separate project or a program (or even a part of the same program as the Architecture Project), but it is not concerned with delivery of an architecture (outputs from the Architecture Project are treated as inputs to Phase G). Phase H (Change Management) is a continuous process concerned with maintaining the architecture and initiating Architecture Projects when necessary and it should be treated as an operational activity. |

An Architecture Project starts with a Request for Architecture Work, which – according to the TOGAF ADM – is an input initiating Phase A. It delivers an Architecture Definition, a Roadmap, and an Implementation Plan. It is finished when these outputs are handed over for implementation.

An Architecture Project can concern one or more architecture domains. The TOGAF Standard defines four architecture domains (Business, Data, Application, Technology) – an Architecture Project typically covers a few or all of them.

An Architecture Project can concern different levels of architecture. The TOGAF Standard defines three levels of architecture – an Architecture Project typically covers exactly one of these:

- Strategic Level: covers the entire enterprise and defines the high-level vision, principles, and strategic directions for the entire Enterprise Architecture

- Segment Level: defines the Enterprise Architecture for a segment (business domain) of the enterprise

- Capability Level: defines the Enterprise Architecture for a single business capability

Enterprise Architecture at this level is the most detailed and leads directly to capability implementation.

Figure 2: Levels of Enterprise Architecture (the TOGAF Standard: Summary Classification Model for Architecture Landscapes)

Architecture developed by an Architecture Project on the strategic level typically is an input to a segment-level Architecture Project. Similarly, segment-level Architecture Projects provide input for capability-level Architecture Projects.

An Architecture Project can be executed as a stand-alone endeavor or as part of a larger effort:

- A stand-alone Architecture Project is usually executed as a separate project (in line with the Project Management regulations of the enterprise)

It has its own set of goals that can be achieved by the project itself (i.e., the Architecture Definition not its implementation). Stand-alone Architecture Projects are often executed on the strategic and segment architecture level.

- Part of a larger effort means that the Architecture Project is a part of a project or program, typically a work stream or a group of tasks

Its key goal is to develop the architecture for implementation within the larger effort. Architecture Projects that are a part of a larger effort are usually executed on the capability architecture level and sometimes on the strategic and segment levels.

|

|

An Architecture Project that is a part of a larger effort does not have to be recognized as a project in terms of the Project Management regulations of the enterprise. More often, it can be a work stream or simply a group of tasks. The approach recommended in this Guide can be applied to both stand-alone Architecture Projects and architecture work that is part of a larger effort. |

Table 1 presents a few examples of real-world Architecture Projects. These examples cover different possible characteristics of an Architecture Project (e.g., level, domains, relationship to other projects).

Table 1: Examples of Architecture Projects

|

Overall Goal |

Architecture Project Overview |

|

(A) Assess current application portfolio and recommend improvement options |

Describe application landscape and identify IT improvement options. There are about 50 applications of different scales (precise number to be determined), mostly custom-built. Key concerns are:

Required views are to be determined. Improvement options should include initiatives with assigned priorities. Timeframe is flexible within 22 weeks maximum. |

|

(B) Improve logistics process efficiency and shorten time-to-order |

Project scope is to model and plan target logistics process improvements to:

The logistics process is one of the core business processes of a transportation company. Three large business units play key roles in the process, each of them divided into about five subunits. The team, apart from a business analyst and an Enterprise Architect, includes a subject matter expert who already understands some parts of this process. |

|

(C) Consolidate IT environment of recently merged businesses |

Define target IT architecture and a three-year roadmap to consolidate merged businesses. Power & Utilities holding includes eight recently merged business units, which distribute and sell energy. These units operate in different areas geographically. They are similar, but each of them has its own business processes and IT applications. Nothing is shared between them. The Architecture Project goal is to formulate a consolidation roadmap, which would include common business services, IT applications, and infrastructure. The approach includes three stages: as-is analysis, to-be modeling, and roadmapping. The Architecture Project must meet defined budget and timeframe constraints. |

|

(D) Define a solution architecture for a Customer Information System supporting a new operating model in a retail sales area of a P&U company |

Analyze changes in an operating model in a retail sales area of a P&U company and requirements for a solution architecture resulting from it. Identify issues with current IT systems supporting this area that prevent the implementation of a new operating model. Develop a solution architecture for a Customer Information System that addresses identified issues and supports the operating model along with a map of data exchange between the system and other IT solutions located in its environment. Develop a tender documentation for a Customer Information System containing the description of the solution architecture. |

|

(E) New management information system to address expanding bank reporting needs |

Define and implement new elastic management information system that will address expanding bank reporting needs and shorten information delay. Project scope includes:

|

These examples were chosen to encompass different kinds of Architecture Projects. Generally, they can be characterized by:

- Levels of architecture[3] covered: Strategic (A, C), Segment (B, D), Capability (E)

- Architecture domains[4] covered: Business (B, C, D, E), Data (B, C, D, E), Application (A, B, C, D, E), Technology (C, D, E)

- Relationship to other projects: stand-alone (A, B, D), part of a larger program (C, E)

These project examples are used throughout Detailed Guidance (Chapter 3) to enhance presented guidance with a practical context. Examples that refer to these projects are denoted using gray boxes.

2.2 Architecture Project Lifecycle

The Architecture Project can be executed as a single, preplanned stage, but usually it is divided into a few stages. Use of stages allows for a more elastic approach, as each of the stages is typically planned in detail just before it starts (rather than at the start of the whole project). The TOGAF Standard advocates iterative execution of Architecture Projects – in this case, each iteration can be considered a separate stage.

|

|

Dividing the Architecture Project into stages is discussed in detail in this Guide. For more information on the iterative approach, refer to architecture development in the TOGAF® Standard – Applying the ADM: Applying Iteration to the ADM. |

The Architecture Project encompasses management activities that can be grouped and sequenced as follows:

- Architecture Project start-up, which raises issues related to appointing the Executive and Project Manager, as well as the Project Management team, capturing previous lessons, selecting the project approach, assembling the project brief, and planning the following stage

- Architecture Project planning, which describes project scoping and planning activities based on Project Management methods

- Planning a stage, which describes how to split an Architecture Project into stages and plan a stage in alignment with an overall Project Plan

- Execute, monitor, and control a stage, which describes how to monitor and control architecture development activities of the ADM Phases B to F using Project Management methods

- Ending a stage, which describes key steps performed at a stage end

- Architecture Project closing (and handover of architecture deliverables for implementation), which describes the project closing activities and handover of the Architecture Project products to implementation programs and projects, and also the approach for documenting lessons learned

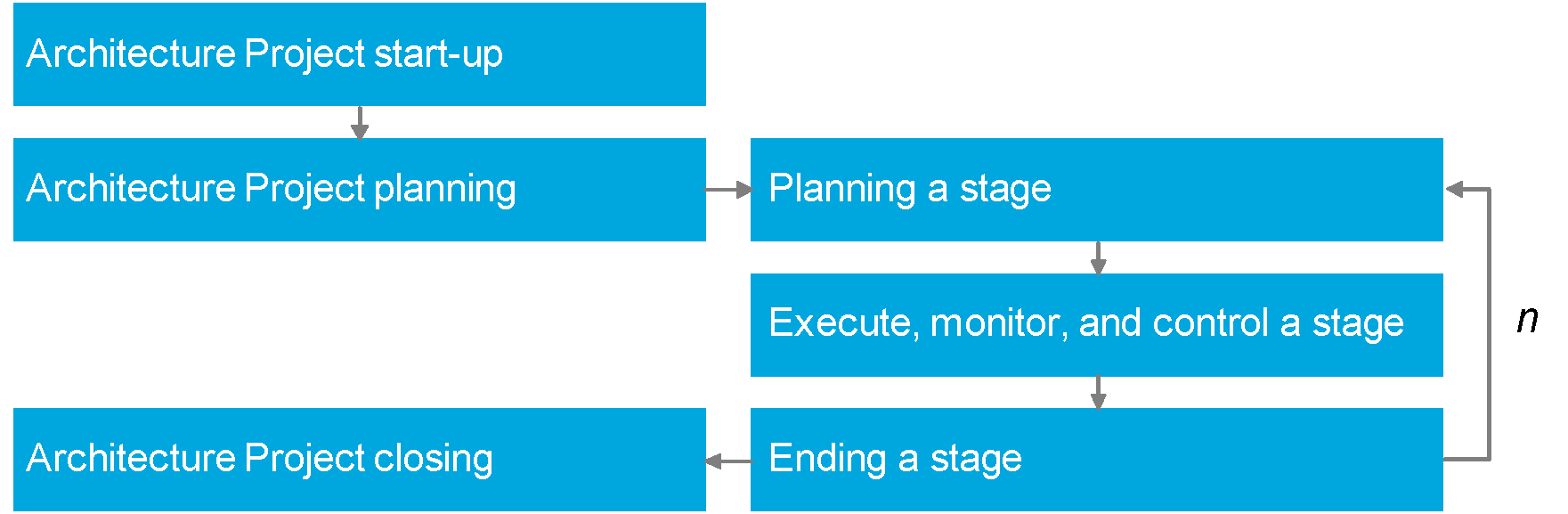

The above sequence forms an Architecture Project lifecycle, which is used as the basic structure to discuss Architecture Project Management in this Guide. This lifecycle maps into the TOGAF ADM (which describes architecture development phases and steps). It can be represented by Figure 3.

Figure 3: Architecture Project Lifecycle from the TOGAF ADM Perspective

|

|

Please note: to simplify Figure 3 it assumes Architecture Project is divided into stages that resemble the ADM phases (each stage covers one ADM phase). Usually, this is not the case – and in most cases should not be; the TOGAF Standard recommends an iterative approach, in which a stage can cover a few phases and can be executed repeatedly. Dividing the Architecture Project into stages is discussed in detail in this Guide. For more information on the iterative approach to architecture development, refer to the TOGAF® Standard – Applying the ADM: Applying Iteration to the ADM. |

The Architecture Project lifecycle also maps to Project Management methods. Generally, these methods abstract from actual subject matter work in the project (i.e., architecture development), as they focus on management processes and steps needed for successful project execution.

|

|

Detailed mapping of the TOGAF ADM and most popular Project Management methods is presented in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 of this Guide. |

High-level mapping of the Architecture Project lifecycle to the TOGAF ADM phases and Project Management methods is presented in Table 2. Please note that the TOGAF Standard focuses on architecture development activities in the Architecture Project, and Project Management methods focus on managing successful execution of this endeavor.

Table 2: Architecture Project Lifecycle Mapped to the TOGAF ADM and Project Management Methods

|

Architecture Project Lifecycle |

TOGAF ADM Phases |

PRINCE2 |

PMBOK |

|

Architecture Project |

Phase A (Architecture Vision) – Establish an Architecture Project step |

Starting up the Project Process – all steps |

Initiation Process group: §4.1 Develop Project Charter §13.1 Identify Stakeholders |

|

Architecture Project planning |

Phase A (Architecture Vision) – Develop a Statement of Architecture Work step and previous steps |

Initiation Process – Create the Project Plan, Assemble the Project Initiation Documentation |

Planning processes from all process groups – create and collect Project Management plan |

|

Planning a stage |

No direct mapping, but can be thought of as a closing step of the preceding phase |

PRINCE2 highlights the concept of project stages more than PMBOK. The concept described in this Guide is mostly based on PRINCE2 processes, but it is also consistent with PMBOK. The Execute, Monitor, and Control a Stage section maps to the Execute and Monitor and Control process groups defined in PMBOK. |

|

|

Execute, monitor, and control a stage |

Each of the Phases B to F |

||

|

Ending a stage |

No direct mapping, but can be thought of as a closing step of the preceding phase |

||

|

Architecture hand-over |

Phase F (Migration Planning) – closing steps |

Closing the Project Process – hand over products |

Closing the project section |

(Source: Derived from the TOGAF Standard, PRINCE2, and the PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition)

To sum up, the Architecture Project lifecycle consists of six types of activities, which can be mapped to both the TOGAF ADM phases and Project Management method processes and steps. It is used to structure the detail presented in Detailed Guidance (Chapter 3).

2.3 Architecture Project Management Concepts

Every method or framework defines its own set of core concepts and definitions. Sometimes they overlap. Sometimes the meaning of overlapping concepts is similar, sometimes not – and they can be considered “false friends” for people who go from one subject matter world to another.

The TOGAF Standard is more recent[5] than the most popular Project Management methods and uses some of the terms and concepts defined by them. In some cases, it gave these terms a new life and there are significant differences in the meaning of some key definitions used throughout the TOGAF Standard and Project Management methods. They are discussed in detail throughout this Guide.

Table 3 presents the TOGAF and Project Management concepts that are key from the perspective of Architecture Project Management. It discusses definitions presented in the TOGAF Standard, PRINCE2, and PMBOK and presents how each term is used throughout this Guide.

Table 3: Key Concepts of the TOGAF Standard, PRINCE2, and PMBOK for this Guide

|

Concept |

Discussion and Definitions |

|

Architecture Project |

As defined earlier in this Guide, an Architecture Project is an endeavor undertaken to define and describe the Enterprise Architecture to be implemented. In TOGAF terms, it encompasses all activities undertaken within the ADM Phases A to F, and Requirements Management for these phases. Practically, it can be a stand-alone project or part of a larger effort (e.g., a program). It has not been defined explicitly in the TOGAF Standard; however, it is used in the framework on a few occasions. There are no corresponding definitions for this concept in Project Management methods. |

|

Deliverables |

Deliverables are unique and verifiable products, results, outputs that are required to be prepared to complete the project or particular phase of the project. Deliverables may be part of the final product, any auxiliary products, or Project Management products. This term is similar in both the TOGAF Standard (where it is more specific, by defining more of the characteristics, acceptance process, etc.) and Project Management methods (more generic), so the most appropriate is the definition from the TOGAF Standard; however, the definitions from Project Management methods are also applicable. TOGAF Standard: “An architectural work product that is contractually specified and in turn formally reviewed, agreed, and signed off by the stakeholders. Note: Deliverables represent the output of projects and those deliverables that are in documentation form will typically be archived at completion of a project, or transitioned into an Architecture Repository as a reference model, standard, or snapshot of the Architecture Landscape at a point in time.” PRINCE2: Synonymous with “Output”, which is defined as: “A specialist product that is handed over to a user(s)”. PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “Any unique and verifiable product, result, or capability to perform a service that is required to be produced to complete a process, phase, or project.” |

|

Executive |

The Executive is the owner of the business goal, responsible for realization of expected benefits, and ultimate success of the project. Its role is comparable with the roles of Sponsor and Executive (which can be considered synonymous with Architecture Sponsor from the Skills Framework) in PMBOK and the TOGAF Standard, respectively, though in the case of PMBOK the involvement of the Sponsor versus Executive is more limited. For the sake of clarity, in this document we will use “Executive” to define such enabling role, no matter what method we refer to in a particular context. TOGAF Standard: No explicitly stated definition, but has named key concerns as “On-time, on-budget delivery of a change initiative that will realize expected benefits for the organization”. PRINCE2: “The single individual with overall responsibility for ensuring that a project meets its objectives and delivers the projected benefits. This individual should ensure that the project maintains its business focus, that it has clear authority, and that the work, including risks, is actively managed.” PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: (Sponsor) “A person or group who provides resources and support for the project, program, or portfolio and is accountable for enabling success.” |

|

Phase |

In this Guide, we use the term “phase” for the TOGAF ADM phases. This is different from the “project phase” term used throughout PMBOK – we use the term “stage” for project phases (see Stage below). TOGAF Standard: Used extensively to describe a collection of logically-related work within the ADM, which is divided into specified phases; e.g., Phase A – Architecture Vision. PRINCE2: No special meaning. PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “A project may be divided into any number of phases. A project phase is a collection of logically-related project activities that culminates in the completion of one or more deliverables.” |

|

Project Manager |

In this Guide, we use the term “Project Manager” to describe a person responsible for ensuring that the project (in this case, Architecture Project) delivers the required product that satisfies the stakeholders’ needs. This constitutes the common part of the definitions from both Project Management methods. The TOGAF Standard does not explicitly define Project Manager, so use of the term based on the Project Management methods was necessary. Please note that the role of Project Manager can be appointed to an Enterprise Architect or to a Project Management professional; refer to the Appoint the Project Manager (Section 3.1.2) for details. TOGAF Standard: No special meaning. PRINCE2: “The person given the authority and responsibility to manage the project on a day-to-day basis to deliver the required products within the constraints agreed with the Project Board.” PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “The person assigned by the performing organization to lead the team that is responsible for achieving the project objectives.” |

|

Risk |

Project risk management is an important aspect of Project Management. According to the PRINCE2 and PMBOK, risk management is one of the key knowledge areas in which a Project Manager must be competent. Project risk is defined by PRINCE2 as “a set of events that, should they occur, will have an effect on achieving the project objectives”,[6] and by PMBOK as “an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on a project’s objectives”.[7] It is important to note that risk impact on a project can be either negative (and actions taken should be focused on minimizing the effect or probability of occurrence) or positive, when we would like to increase the impact or probability of occurrence of such an event. Risk and compliance are an inherent part of any business activity or transformation, thus the TOGAF Standard requires proper consideration throughout the ADM, as defined in the Architecture Capability Framework. The key difference is that the TOGAF Standard understands risk as a potential threat of the transformation to the technical environment and compliance, while PRINCE2 and PMBOK are also considering risk as an event that can affect the project itself (timeline, budget, quality, etc.). |

|

Scope |

In this Guide, we use the term “scope: as defined in the Project Management methods. This is a broader meaning than described in the Define Scope step of the TOGAF ADM Phase A, and it means the scope of work that is to be performed in order to achieve projects goals. In contrast, the TOGAF Standard restricts use of the term scope to the scope of the architecture to be defined. TOGAF Standard: The Define Scope step of the ADM Phase A restricts the scope definition to the scope of architecture: “what is inside and what is outside the scope of the Baseline Architecture and Target Architecture efforts”. PRINCE2: “The scope of a plan is the sum total of its products and the extent of their requirements. It is described by the product breakdown structure for the plan and associated product descriptions.” PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “The sum of the products, services, and results to be provided as a project.” |

|

Stage |

In this Guide, we use the term “stage” for stages (as defined in PRINCE2) or project phases (as defined in PMBOK). We do not use the term “project phase” as we reserve it for the TOGAF ADM phases (see Phase above). TOGAF Standard: No defined meaning. PRINCE2: “A section of a project.” PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: No defined meaning. |

|

Stakeholder |

The meaning of stakeholder in the TOGAF Standard and Project Management methods is generally the same. The TOGAF Standard, as an architecture lifecycle standard, highlights that the stakeholder focuses on the outcomes of the architecture. TOGAF Standard: “An individual, team, organization, or class thereof, having an interest in a system.”[8] PRINCE2: “Any individual, group, or organization that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by, an initiative (program, project, activity, risk).”[9] PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “An individual, group, or organization who may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome of a project.”[10] |

|

Work Package |

The TOGAF Standard uses the term work package to describe change initiatives that will be implemented in the enterprise. These initiatives are typically large groups of tasks (i.e., they may encompass a whole program). Project Management methods use the term work package to describe a low-level part of work to be performed – the most granular part of work that needs the Project Manager’s authorization before it is started by the team. The two meanings are vastly different. In this Guide, we use the term “Project Work Package” for project tasks (in line with the PRINCE2 use of the term and the PMBOK definition below) and “work package” for change initiatives identified by Architecture Projects (in line with the TOGAF definition below). TOGAF Standard: “A set of actions identified to achieve one or more objectives for the business. A work package can be a part of a project, a complete project, or a program.” PRINCE2: “An input or output, whether tangible or intangible, that can be described in advance, created, and tested.” PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition: “The work defined at the lowest level of the work breakdown structure for which cost and duration can be estimated and managed.” |

(Source: Derived from the TOGAF Standard, PRINCE2, PMBOK Guide, 5th Edition)

In this Guide we use concepts from both Enterprise Architecture (TOGAF Standard) and Project Management (PRINCE2, PMBOK) disciplines. As this Guide is addressed primarily to architects, in case of conflicts, we usually stick to the TOGAF definitions. If you have a different background, please keep Table 2 in mind.

2.4 Project Management Documentation

Project Management is about communication. The Project Manager is responsible for communicating project plans, statuses, and risks to project stakeholders – the Project Sponsor, Steering Committee, and other stakeholders. This can be effectively achieved formally or informally, and in many forms – such as phone calls, meetings, presentations, or written reports. It depends on project size, organizational culture, and stakeholder requirements among other things.

In this Guide, we often refer to plans, reports, and other artifacts that can or should be documented. This does not mean every such artifact should be a separate document. In smaller projects and more agile organizations, very little documentation may be required or necessary. However, we do recommend that Project Management artifacts are documented in a written form, even as simple as email. This allows for tracing back plans, important decisions, and project milestones. In addition, documentation that is more formal can be prepared based on it, if necessary.

This section describes a detailed Project Management approach to use when developing Enterprise Architecture. The target audience of this section is Enterprise Architects who are already familiar with the TOGAF Standard and who lead Architecture Projects.

This section is organized into subsections which describe the approach to:

- Architecture Project start-up, which includes the Project Management activities of the ADM Phase A and the project start-up and “Initiation” activities of the Project Management methods

- Architecture Project planning, which includes project planning activities based on the Project Management methods

- Planning a stage, which describes how to apply the Project Management methods to plan an Architecture Project stage

- Execute, monitor, and control a stage, which describes how to monitor and control the architecture development activities of the ADM Phases B to F using the Project Management methods

- Ending a stage, which describes how to apply the Project Management methods at the end of an Architecture Project stage

- Architecture Project closing, which includes project closing activities of the Project Management methods and the ADM Phase F, including handover of architecture deliverables for implementation

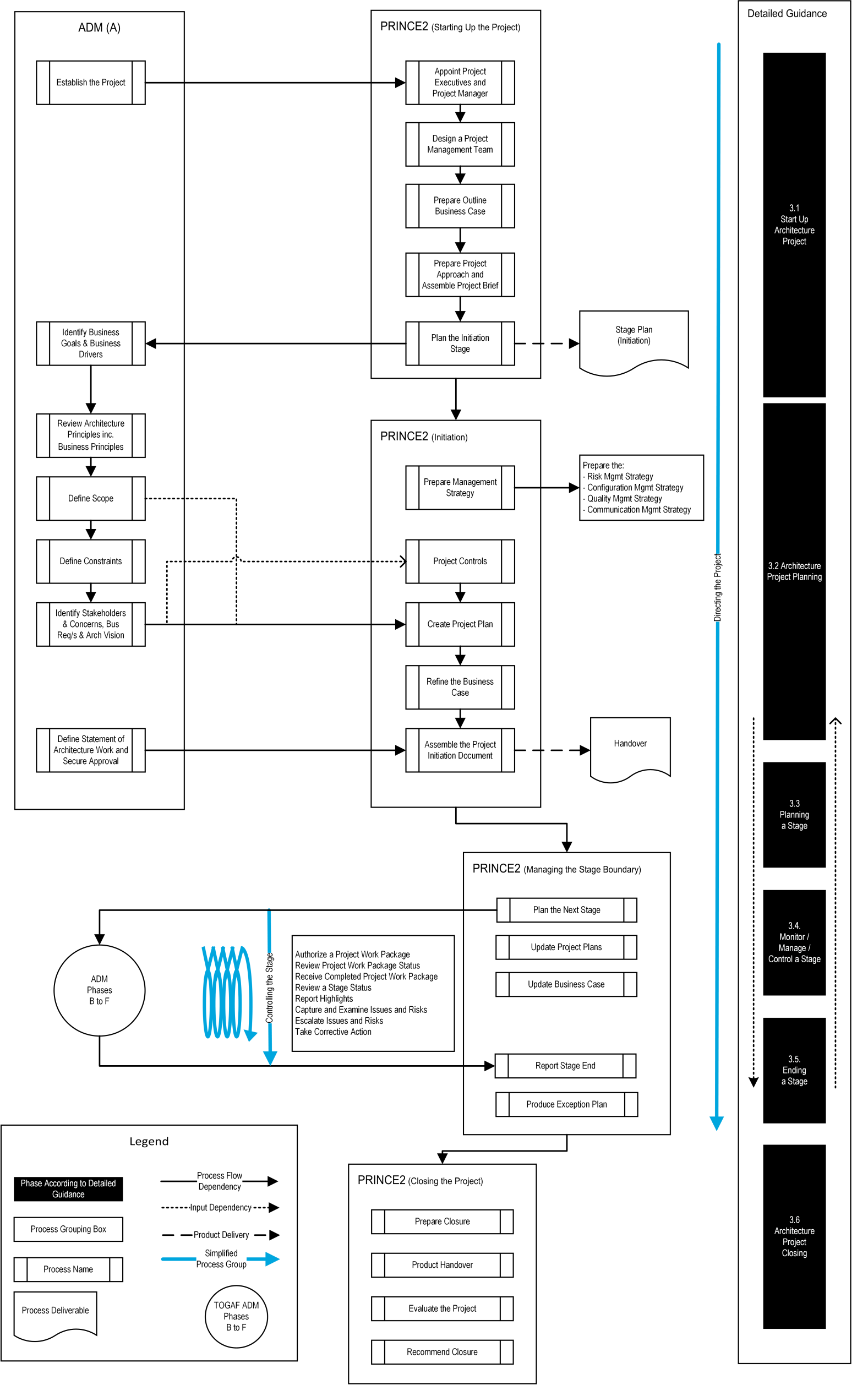

Figure 4: Structure of this Section and Architecture Project Flow (arrows)

Where appropriate, guidance refers to one or more real-world examples. These examples are presented in gray boxes. They refer to selected projects from our examples list (see Table 1).

|

|

The approach in this Guide covers most of the Project Management responsibilities related to an Architecture Project; however, some areas – such as schedule management, procurement management, cost management, and others – are not covered. We assumed that the purpose of this Guide is not to explain the Project Management methods in full detail, but to provide guidance on how to apply them in the reality and characteristics of Architecture Projects. Since areas related to procurement, cost, etc. are not different from other projects, they are not detailed in this Guide. |

3.1 Architecture Project Start-Up

The first step of Phase A of the ADM cycle is defined in the TOGAF Standard, Phase A: Establish the Architecture Project. The chapter is very concise and refers the reader to other sources, by stating: “execution of ADM cycles should be conducted within the Project Management framework of the enterprise”. It does not detail steps to be undertaken at the very beginning of the Architecture Project, but leaves it to the Project Manager and other bodies within the enterprise to decide on what has to be done based on their experience and a set of organizational standards.

According to PRINCE2 to ADM Mapping (Chapter 4), the ADM step Establish the Architecture Project can be mapped to the PRINCE2 Starting up a Project process. PMBOK, due to its different nature, does not provide such elaborate systematic processes, nevertheless its Develop Project Charter process can be mapped to this TOGAF step as well (see PMBOK to ADM Mapping, Chapter 5). Therefore, the following activities are necessary for starting up a project:

- Appoint the Executive and Project Manager

- Capture Previous Lessons

- Prepare Outline Business Case

- Select the Project Approach

- Design and Appoint the Project Management Team

- Assemble the Project Brief

- Define the Management Approach

The above-mentioned activities form a basis for the following subsections.

3.1.1 Appoint the Executive

The project should be a response to an identified business need, as its execution is connected with tangible and usually quantifiable costs for the organization, in the form of, for example, cash expenditure, man-hours of employees, and even disruptions in normal operations. The project can only be executed when there are necessary resources provided, usually on the assumption that they will achieve some business goal and provide sufficient return in some form (like business benefits, ability to continue operations, etc.).

|

Example |

There are multiple possible benefits of Architecture Projects; for example:

which all stem from having good, thoroughly planned Enterprise Architecture (or, at the very least, are facilitated by it) or undertaking architectural efforts. In other cases, Architecture Projects are enablers of other initiatives, projects, and programs, and do not deliver value on their own, or are just necessarily grounded in external factors (like compliance with regulatory requirements). |

The Executive is the owner of the project’s business goal, and therefore an incarnation of organizational support for the initiative at hand, responsible for realization of expected benefits. Depending on the organization (especially its Project Management framework) and the project itself (its type), the Executive can have different names and structures. The term was originally taken from the PRINCE2 method, where it is the name of the role representing the “Customer”, who is the ultimate resource provider for the project.[11] A very similar role, though more limited, is played by the “Sponsor” in PMBOK. The same is the case with the TOGAF Standard, where the Executive is responsible for ensuring “on-time, on-budget delivery of a change initiative that will realize expected benefits for the organization”.[12]

The TOGAF Standard does not elaborate on the Executive much. It is named as a stakeholder organizational role, which can be played by, for example, a sponsor or program manager. It defines the necessary skill set (see the TOGAF® Series Guide: Architecture Skills Framework (Goals/Rationale)) in the skills framework, provides information on the sponsorship of the initial Enterprise Architecture effort (namely that it is usually a CIO or other Executive), names the sponsor of the architecture (Architecture Board), as well as the “sponsor of sponsors” (Executive sponsor from the highest level of the corporation).

As pointed out earlier, there can be no project without an Executive, who provides the necessary resources for the project’s execution and represents the need to be addressed. The Executive is the person that appoints the Project Manager and tasks them with Architecture Project execution at the operational level.

|

Example |

Examples of Architecture Project Executives are:

|

3.1.2 Appoint the Project Manager

As stated in the Appoint the Executive step above, the Project Manager is appointed by the Executive to lead the Architecture Project on the operational level.

A Project Manager is a person responsible for ensuring that the project delivers the required product that satisfies the stakeholders’ needs. Therefore, a Project Manager must have strong leadership, communication, and negotiation skills in order to lead the stakeholders to the project’s successful outcome.

|

|

According to PRINCE2, the Project Manager is a person given the authority and responsibility to manage the project on a day-to-day basis to deliver the required products with the constraints agreed with the Project Board. The Project Manager’s prime responsibility is to ensure that the project produces the required products within the specified tolerances of time, cost, quality, scope, risk, and benefits. The Project Manager is also responsible for the project delivering a result capable of achieving the benefits defined in the business case.[13] According to PMBOK, the Project Manager is a person assigned by the performing organization to lead the team that is responsible for achieving the project objectives. In general, Project Managers have the responsibility to satisfy the needs: task needs, team needs, and individual needs.[14] |

A common question is: who should be an Architecture Project Manager? Project Management methods advocate assigning such a role to a Project Management professional.

The TOGAF Standard does not answer this question, but the Architecture Skills Framework[15] provides an assessment of the skills required to deliver a successful Enterprise Architecture. According to the framework, the Enterprise Architect is responsible for ensuring the completeness (fitness-for-purpose) of the architecture, in terms of adequately addressing all the pertinent concerns of its stakeholders; and the integrity of the architecture, in terms of connecting all the various views to each other, satisfactorily reconciling the conflicting concerns of different stakeholders, and showing the trade-offs made. Therefore, for most Architecture Projects, the role of an Enterprise Architect satisfies the definition of the Project Manager. In addition, excellent communication with stakeholders required from the Enterprise Architect lowers the need to designate a dedicated Project Manager that is typical for IT projects.

However, in some cases there may be a need to delegate Architecture Project Management and control to a dedicated Project Manager. The decision to include a dedicated Project Manager in an Architecture Project will depend on the Project Management rules and principles adopted in the organization, the scale of the Architecture Project, the number of internal entities and external suppliers involved in the project, the number of project streams, its timeframe, etc. You may find that the Architecture Project is so complex that combining an Enterprise Architect role with the Project Manager role may not be effective because the workload connected with managing and controlling the project according to the organization’s Project Management rules and principles limits the Enterprise Architect to focus on core architecture work.

|

Example |

In Project B, an Enterprise Architect served as a Project Manager. This was possible due to the low complexity of the project – it covered only one business domain, engaged people from three business units, and five to ten IT systems. Moreover, the Project Management rules and principles adopted in the organization were focused only on reporting issues and risks associated with delivering the project within the specified tolerances of time and cost. In Project D, there was a need to include a dedicated Project Manager due to the complexity of the project – it consisted of five work streams (architecture was one of them) whose products were inter-dependent, covered over 25 IT systems, and engaged over 50 people from various business units. The Enterprise Architect was responsible for managing the work in the architecture stream and reporting its status to the Project Manager who was, among others, responsible for consolidating status reports from all streams and presenting an overall status of the project to its stakeholders on a weekly basis. |

In the rest of this Guide, we use “Project Manager” for a role responsible for the execution of the Architecture Project. This role can be assigned to an Enterprise Architect or to a Project Management professional, as discussed above.

3.1.3 Capture Previous Lessons

One of the first things the Project Manager is expected to do after being appointed, as per the PRINCE2 method, is preparation of a Lessons Log.[16] This document should function as an informal repository of knowledge about the current project. At the very beginning, it should be completed with all relevant information available about similar projects, including key information from previous projects’ Lessons Logs (or Lessons Reports, if these exist) and other relevant documentation, experiences of people involved in such endeavors, and all other potential sources of knowledge (in case of Architecture Projects, the input should be obtained, among other sources, from the lessons learned documented in Phase F.[17]) It enables the Project Manager to gain better insight into the nature of the project and better prepare and execute the project by avoiding mistakes made previously by others and using developed know-how.

The document should undergo regular updates when it should be filled in with additional information acquired as well as developed good and best practices, which will support the Project Manager in his duties on this and other projects.

The level of detail in this document should be adequate to the requirements of the project (its scale and complexity) and compliant with the internal regulations of the particular organization. There is no need to create sophisticated Lessons Logs for small projects. In some cases even a bullet list, containing the most important observations, might be sufficient.

|

Example |

The Project Manager has been appointed to manage the project focusing on the architecture design and implementation of a new Data Warehouse and Management Information System (Project E). As a first step, the Project Manager gathered information about the project at hand and interviewed the Sponsor. In order to ensure integrity, completeness, and constant availability of potentially useful information, he created the Lessons Log, where he intended to put all the information he considered useful at the beginning, and where he will include all the insights gained during the project execution. As it turned out, there was another project executed in the company, which resembled the current project in scope and budget and ended in failure due to not being completed in the estimated time. The documented reason for that was tasking the main architect with Project Management duties, which proved to be too much to handle for one person in this project type and set-up. The Project Manager included the note in the Lessons Log: “In projects with such scope, the Project Management and Enterprise Architecture duties should be separated; otherwise, there is a risk of neither of these functions being executed properly due to the excessive workload.” |

3.1.4 Prepare Outline Business Case

Simultaneously, the PRINCE2 method expects the preparation of an outline business case, which will be an integral part of the Project Brief, providing information on expected costs, risks, and benefits of the project. The outline business case is an attempt at providing quantitative and qualitative assessment of the project, enabling the decision-makers (i.e., the Executive or similar body) to make a more informed choice about whether the project is feasible and beneficial, and whether it is the best project to undertake from the whole portfolio of project ideas.

The document is a responsibility of the Executive, though it does not mean that they prepare it. This task might be delegated to, for example, business analysts or the Project Manager.

This document should become more detailed later on, as additional planning efforts are conducted, and should be regularly verified and continuously maintained to provide the current state of knowledge about all factors that might affect the outcome of the project. This constitutes a basis for strategic decisions regarding the project, including a decision on whether the continuing project is still beneficial, feasible, and needed (see Execute, Monitor, and Control a Stage, Section 3.4). After the completion of the project, the business case should also be confirmed, to see whether the forecasts regarding benefits were correct (see Architecture Project Closing, Section 3.6).

|

Example |

The Project Manager has been tasked with creating the business case for Project C (Consolidate IT environment of recently merged businesses). The newly created IT environment is largely redundant, allowing for a significant reduction of IT costs through application and infrastructure consolidation. Possible savings are estimated at 20-50M EUR yearly. The Architecture Project that will define the target model and consolidation roadmap is estimated to involve four FTE of Enterprise Architects and eight FTE of other staff for six months (total cost of 0.5M EUR including expected risk materialization costs). The resulting roadmap implementation is estimated to cost between 40M and 100M EUR. The Project Manager has documented these preliminary findings in an outline business case and communicated them to the Executive, mentioning that these require further analysis, but the project looks promising and should be, in his opinion, continued, at least until a more precise cost benefit analysis can be prepared based on Architecture Project findings. |

3.1.5 Select the Project Approach

PRINCE2 expects the Project Manager to select the approach to project execution. Decisions to be made mentioned by the PRINCE2 method are, among others: what resources to use (internal or external), whether to build a solution from scratch or modify existing solutions, or whether to base it on a Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) solution, or create a tailor-made one.

In the case of Architecture Projects, only the first decision is relevant. However, from the perspective of Architecture Project Management, the approach should be understood more broadly: what methods and frameworks should be used to manage the Architecture Project and how to plan the project.

The choice of methods and frameworks used in the Architecture Project Management should stem from the characteristics of the problem the project aims to solve and be connected with the adopted planning approach. Since the area of Architecture Project Management is a composite of Project Management and Enterprise Architecture fields, decisions should be made regarding tools used in each of these domains.

1. Choosing the Resources to Use

From our experience, the decision on whether to use internal or external resources should be made taking into consideration at least the following:

- Estimated complexity of the project and amount of work needed

- Time and budget constraints

- Necessary skills – note that knowledge of the existing architecture may be highly relevant; cost of obtaining it (i.e., current state analysis) should be carefully considered for external consultants

- Available resources inside the organization

- Previous experiences and organizational guidelines

|

Example |

The Project Manager tasked with managing Project E has concluded that due to broad estimated scope, high complexity, and difficulty of the project, as well as strict time constraints resulting from legal obligations of the bank, the project requires multiple architects with high competency in the data domain. The resources at hand were assessed as insufficient and there was neither possibility to recruit more people in time, nor to train the available architects to the adequate skill level. The Project Manager has decided to approach the project using external resources by engaging a group of architects from the consulting firm, with which the bank has a longstanding, positive relationship and has successfully completed other projects. |

2. Choosing a Planning Approach

The decisions regarding planning approach and methods/frameworks are inter-dependent, as each may influence the other. The TOGAF Standard advocates an iterative approach with iterations repeated until the product achieves the expected quality and consistency, which many people equate with the agile approach and methods. This is not the case, and there is no fundamental contradiction between the proposed approach and the waterfall methods. Nevertheless, it might require tailoring of the TOGAF framework to fit within the constraints of the Project Management methods and particular projects. For more information on how to plan the project, with particular focus on dividing it into stages, refer to Architecture Project Planning (Section 3.2) and Planning a Stage (Section 3.3).

3. Choosing a Method

Useful in the case of choosing the best approach (from the Project Management method viewpoint) to the particular problem could be the Cynefin Framework. It divides the so-called problem domain into four main categories: complex, complicated, obvious (simple), and chaotic.[18] Depending on the category of the problem, different methods are recommended, due to them being best suited for different circumstances as they have different strengths and weaknesses. In our experience, the following methods are recommended for particular problem categories:

- Complex – SCRUM method, specifically designed to deal with a high level of volatility and uncertainty

- Complicated – e.g., Kanban and SCRUM methods, as the category covers sophisticated problems, requiring careful analysis, highly expert knowledge to solve, and some amount of probing different solutions, as there is no one best solution

- Obvious (simple) – all of the waterfall approaches, as the category covers known problems and has best practices prepared, enabling use of a carefully preplanned approach

- Chaotic –no method recommended, due to complete unpredictability of the systems’ behavior

Problems in the area of Enterprise Architecture tend to fulfill the criteria for simple and complicated categories, especially when architecture is already present in the organization, as it aims at increasing the level of order and predictability. The cause-and-effect relationships are present and possible to discern, and the only case in which the problems might become complex or chaotic is high volatility of the environment (usually combined with lack of knowledge about the organization at hand and its exterior). To which domain a particular problem belongs depends, inter alia, on the expertise in the organization, its architecture maturity, scope of the project, and additional constraints imposed. The task to classify the problem is up to the Project Manager.

4. Choosing an Enterprise Architecture Framework

In the area of Enterprise Architecture, the choice to be made is between one of different architecture frameworks. There are at least a few different major frameworks which provide tools and resources for Enterprise Architects (including the Zachman Framework and the Federal Enterprise Architecture (FEA)). However, not all of them are useful in the case of Architecture Project Management. This is the consequence of the different focus of each of the frameworks. As Architecture Project Management is, in fact, a process of creating an architecture, only the frameworks which provide methods of creating architectures should be taken into consideration. This is where the TOGAF framework, as compared to other frameworks, excels, thanks to its detailed description of the ADM.

|

Example |

In Project A, the Project Manager has no clear understanding what views are necessary to achieve the goals of the project, making it a complicated problem. He therefore has decided to include on “overview” stage at the beginning, enabling him to determine scope, which will allow completion of the project in the set timeframe and with set resources. After the thorough analysis of two applications during this phase, he confirmed with the Executive what is feasible to do in the following stages and will address the existing business need of the Executive. Later on, the Project Manager has decided to adopt an iterative approach by splitting the 50 applications used into groups of eight, which will be assessed in every two-week iteration. In Project E, the Project Manager has to deliver precisely described artifacts and products to a set date, making the problem a simple one, assuming the presence of necessary resources. Failure to do so will result in potentially costly delays in the project, including fines for not complying with regulatory requirements, as the architecture stream is on the critical path. Therefore, the Project Manager has adopted the preplanned approach with time-bound stages with some buffer, focusing initially on the baseline (baseline first approach). This plan has been assessed as feasible by the external consulting experts involved in the project, who have participated in similar projects in the past. Nevertheless, the risk has been assessed and communicated, and its significant part has been transferred to the consulting firm in the form of additional provisions in the contract. |

In this Guide we assume the Architecture Projects are conducted according to the TOGAF framework, supplemented with practices stemming from the most popular Project Management methods.

3.1.6 Design and Appoint the Project Management Team

Project Managers of Architecture Projects do not operate in a void and do not deliver products singlehandedly. They use support provided by other institutions within an enterprise and are regulated by them in order to ensure that the goals of the organization are met. They are part of the team, working together to deliver the products and realize the benefits for the organization.

In PRINCE2, they are part of a Project Management Team, which provides them with oversight and support. These Project Management Teams are the whole Project Management structure comprising bodies responsible for governance,[19] management, and support. There are also Project Management Teams in PMBOK, but, in comparison to PRINCE2, they are limited to Project Management and leadership activities, and do not include governance bodies (they only cooperate with them).

Figure 5: Simplified Chart Representing Model Project Team Based on the PRINCE2 Method

1. Governance in Architecture Projects

The bodies which are responsible for successful delivery of the product should naturally be the ones most interested in “ensuring that the business is conducted properly” (which is the most general definition of governance, found also in the TOGAF Standard). This is exactly the case: the governing body in the case of PMBOK is the Sponsor, in PRINCE2 it is the Steering Committee, led by an Executive (who is the ultimate decision-maker, only advised by optional representatives of users and suppliers), and in the TOGAF Standard it is the Architecture Board (which is a sponsor of architecture in an enterprise).

It is necessary to bear in mind, though, that there is a difference in the type of governance provided by the Architecture Board (i.e., Architecture Governance) and the other two bodies mentioned (i.e., Project Governance). Architecture Governance is the practice and orientation by which Enterprise Architectures and other architectures are managed and controlled at an enterprise-wide level, while Project Governance (according to PMBOK) is an “oversight function that is aligned with the organization’s governance model and that encompasses the project lifecycle … providing a comprehensive, consistent method of controlling the project and ensuring its success”. As a result, Architecture Projects should be subject to both types of governance, first allowing to provide alignment with strategic architecture and sub-architectures, second to ensure that the project delivers expected results in terms of quality, budget, and time.

Does this mean that the Project Manager on the Architecture Project should be overseen by two different bodies? Often yes. However, it depends on the Project Management and Enterprise Architecture organization. Is the architecture governance body (such as the Architecture Board) already established in the organization? If it is, can the architecture governance body take the role of project governance as well? If it is not and the project is the organization’s initial Enterprise Architecture effort, can the Steering Committee transform into an Architecture Board after the project is completed? There are many possibilities and the approach should be different depending on project and organization characteristics.

|

Example |

The Project Manager has been tasked with managing Project B (improve logistics process). The project is sponsored by the CIO of the company, who has been tasked by the business to provide current information to allow for better planning and resource allocation, to shorten order-to-delivery time as an end result. The CIO presides over the Architecture Board, which also includes some leaders of business units involved in the company’s logistics process. The CIO decided there is no need to set up additional bodies to provide project governance, as most of the key stakeholders are already part of the body providing architecture governance. There are no inter-dependencies or planned follow-ups at the moment, and all decisions will be made on the basis of its outcome. As a result, the Project Manager turns to the Architecture Board and CIO in particular to provide not only architecture governance, but also project governance as a Sponsor of the project, and, if possible, to include the rest of the affected business leaders on the Board. |

|

Example |

The Project Manager has been ordered to lead Project E, aiming to design the to-be architecture in a bank, which includes new data warehouse and management information systems. The Architecture Project is part of a larger program of new solution implementation, making architecture effort only one of multiple streams, which are closely related and dependent on each other. This is especially true for the Architecture Project, which functions as an enabler for further work. The project has been initiated by the Program Management of the whole information system transformation initiative, which is not in any way connected with the Architecture Board. It is strictly bound by budget, timeframe, and scope, requiring strict adherence to the plans and requirements. The Project Manager is responsible in this case to the Program Management, while simultaneously has to adhere to the rules and constraints imposed by the Architecture Board in the organization. Depending on the type of issue, whether it is connected with architecture, or Project Management and execution, he is obliged to follow different escalation routes. |

2. Project Manager’s Support in Architecture Projects

Sometimes, Architecture Projects are too big and complex for a single Project Manager to undertake and manage, even with support provided from the enterprise leadership. Furthermore, some projects may require specific skills and competencies, which are not possessed by the Project Manager designated to lead the project. This creates the need for additional people, other than those in the Architecture Board or other governing body, who ultimately become the core of the Project Management Team.

The TOGAF Standard describes the roles that are usually part of an “architecture team” in the TOGAF® Series Guide: Architecture Skills Framework: Enterprise Architecture Role and Skill Categories, and Enterprise Architecture Role and Skill Definitions. These include both roles responsible for governing the architecture and supporting the project and roles responsible for operational management and delivery (architects for different domains and solution designers). These roles are part of the Architecture Capability Framework and are separate from the structure of a Project Management Team. The TOGAF Standard does not describe how the Project Management Team supporting the project should be staffed or organized. However, some hints are provided in the Project Management methods.

PMBOK provides general information about Project Teams[20] in Section 2.3 and hardly any regarding Project Management Team (a subset of Project Team responsible for the Project Management and leadership activities). It says that the only constant with regards to the Project Team is Project Manager’s role as its leader, giving a lot of freedom to the Project Manager. Among the factors which should be considered while devising the Project Team structure, PMBOK mentions culture, scope, location, and organizational structure. It does not provide guidelines on how it should be organized, other than giving information on some of possible roles within the Project Team (for more information, see Section 2.3 of the PMBOK Guide) and tools supporting the Project Manager’s decision-making and management processes (see Chapter 9 of the PMBOK Guide).

PRINCE2 is more specific and points out team managers, who are people responsible for delivery of products assigned by the Project Manager, as defined in the Project Work Packages later on (for more information on Project Work Packages and Work Packages see Architecture Project Management Concepts, Section 2.3) and people being part of Project Support (usually as part of the Project Management Office), whose duties are limited to support in administration and operations and providing guidance regarding Project Management tools and techniques).

The decision on whether to appoint team managers, how to define their roles and duties, is entirely up to the Project Manager (but this decision should be approved by the bodies providing project governance), but shouldn't be made without serious consideration, as it impacts how the work will be divided during the project. The factors, which should be considered are, among others:

- Estimated scope of the project, with regard to both domains and segments, that will be affected by the project

- Project constraints, especially with regard to timeframe

- Size of the team involved

Based on what we know about Architecture Projects and having a general knowledge of Project Management methods, it is possible to propose at least two ways of selecting team managers:

- By architecture domain, where particular team managers are architects responsible for either business, data, application, or technology architecture

- By enterprise continuum level, where particular team managers are architects responsible for different segments or solutions, which are affected by the project (however, we recommend that the Architecture Project has a clear scope restricted to one of the levels: strategic, segment, or capability)

|

Example |

In Project E, architecture is just one of work streams of a large project. The architecture work stream can use a general Project Support team (PMO) for administrative tasks such as setting up meetings or managing the work stream repository. Therefore, the architecture work stream leader decided he would not need any separate support staff. |

The team structure is established in the Project Start-up stage. However, after the initial stages of the project, the Project Team structure should be reviewed and may be adapted to changing needs.

3. Delivery Team in Architecture Projects

The last group (but no less important than those mentioned earlier) are people engaged in operational execution by working on project deliverables. They are organized in teams, managed by the Project Manager directly or team-level managers, depending on the Project Management structure in a particular project.

Selection of people to be involved in the project is critical to its success. It depends mainly on the goals and scope of the Architecture Project, and the resources available. The TOGAF® Series Guide: Architecture Skills Framework can be helpful in planning and selecting delivery team members. More general techniques in this area are described in the PMBOK Guide, Chapter 9.

|

Example |

In Project B, the delivery team was selected among available resources. The aim was to ensure the team has skills strong enough to cover each of the business subunits with a single workshop. This required careful planning and the right mix of skills and knowledge of current information flows and systems within the team. The delivery team consisted of:

|

3.1.7 Assemble the Project Brief

According to PRINCE2 and PMBOK, the project becomes authorized when a document summarizing the project’s assumptions is assembled and approved. At minimum, the document should define the high-level boundaries of the project.

|

|

According to PRINCE2, the Project Brief is a statement that describes the purpose, cost, time, and performance requirements, and constraints for a project.[21] According to PMBOK, the project becomes authorized when the Project Charter is approved. The Project Charter documents the business needs, assumptions, constraints, the understanding of the customer’s needs and high-level requirements, and the new product, service, or result that it is intended to satisfy. |