Preface

The Open Group

The Open Group is a global consortium that enables the achievement of business objectives through technology standards. With more than 870 member organizations, we have a diverse membership that spans all sectors of the technology community – customers, systems and solutions suppliers, tool vendors, integrators and consultants, as well as academics and researchers.

The mission of The Open Group is to drive the creation of Boundaryless Information Flow™ achieved by:

- Working with customers to capture, understand, and address current and emerging requirements, establish policies, and share best practices

- Working with suppliers, consortia, and standards bodies to develop consensus and facilitate interoperability, to evolve and integrate specifications and open source technologies

- Offering a comprehensive set of services to enhance the operational efficiency of consortia

- Developing and operating the industry’s premier certification service and encouraging procurement of certified products

Further information on The Open Group is available at www.opengroup.org.

The Open Group publishes a wide range of technical documentation, most of which is focused on development of Standards and Guides, but which also includes white papers, technical studies, certification and testing documentation, and business titles. Full details and a catalog are available at www.opengroup.org/library.

The TOGAF® Standard, a Standard of The Open Group

The TOGAF Standard is a proven enterprise methodology and framework used by the world’s leading organizations to improve business efficiency.

This Document

This document is a TOGAF® Series Guide to Value Streams, addressing how to identify, define, model, and map a value stream to other key components of an enterprise’s Business Architecture. It has been developed and approved by The Open Group.

This Guide is structured as follows:

- Chapter 1 (Introduction) introduces the concept of value, how it relates to business in general, and how it can be used and applied within Business and Enterprise Architecture

- Chapter 2 (Value Stream Description, Decomposition, and Mapping) describes the structure and mechanics of the value stream, including its decomposition into value stream stages

- Chapter 3 (Approach to Creating Value Streams) sets out guiding principles for constructing a value stream map

- Chapter 4 (Value Stream Mapping Scenarios) describes a range of business scenarios and practical examples of value stream mapping

- Chapter 5 (Conclusion) summarizes the role and value that value streams and value stream mapping can bring to business

- Appendix A (Comparison of Alternative Value Analysis Techniques) compares and contrasts other common value analysis techniques used in business, including the value chain, value network, and the Lean value stream

The intended audience for this Guide is as follows:

- Enterprise Architects

- Business Architects

- Process modelers

- Strategy planners

About the TOGAF® Series Guides

The TOGAF® Series Guides contain guidance on how to use the TOGAF Standard and how to adapt it to fulfill specific needs.

The TOGAF® Series Guides are expected to be the most rapidly developing part of the TOGAF Standard and are positioned as the guidance part of the standard. While the TOGAF Fundamental Content is expected to be long-lived and stable, guidance on the use of the TOGAF Standard can be industry, architectural style, purpose, and problem-specific. For example, the stakeholders, concerns, views, and supporting models required to support the transformation of an extended enterprise may be significantly different than those used to support the transition of an in-house IT environment to the cloud; both will use the Architecture Development Method (ADM), start with an Architecture Vision, and develop a Target Architecture on the way to an Implementation and Migration Plan. The TOGAF Fundamental Content remains the essential scaffolding across industry, domain, and style.

Trademarks

ArchiMate, DirecNet, Making Standards Work, Open O logo, Open O and Check Certification logo, Platform 3.0, The Open Group, TOGAF, UNIX, UNIXWARE, and the Open Brand X logo are registered trademarks and Boundaryless Information Flow, Build with Integrity Buy with Confidence, Commercial Aviation Reference Architecture, Dependability Through Assuredness, Digital Practitioner Body of Knowledge, DPBoK, EMMM, FACE, the FACE logo, FHIM Profile Builder, the FHIM logo, FPB, Future Airborne Capability Environment, IT4IT, the IT4IT logo, O-AA, O-DEF, O-HERA, O-PAS, Open Agile Architecture, Open FAIR, Open Footprint, Open Process Automation, Open Subsurface Data Universe, Open Trusted Technology Provider, OSDU, Sensor Integration Simplified, SOSA, and the SOSA logo are trademarks of The Open Group.

A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge, BIZBOK, Business Architecture Guild, CBA, and Certified Business Architect are registered trademarks of the Business Architecture Guild.

All other brands, company, and product names are used for identification purposes only and may be trademarks that are the sole property of their respective owners.

About the Authors

This document was developed by the Business Architecture Work Stream of the Architecture Forum, a forum of The Open Group.

(Please note affiliations were current at the time of approval.)

Alec Blair – Program Lead, Enterprise Architecture, Alberta Health Services

Alec has been working as an Enterprise Architect and Enterprise Architecture manager/coach for the last 15 of his 28 years in the IT industry. Alec currently leads the Alberta Health Services Enterprise Architecture community of expertise and is a Certified Business Architect® (CBA®). This virtual team spans more than 40 practitioners working on all dimensions of Enterprise Architecture.

J. Bryan Lail – Raytheon

J. Bryan Lail is a Business Architect Fellow at Raytheon. He is a Certified Business Architect® (CBA®) with the Business Architecture Guild®, a Master Certified Architect with The Open Group, and a Raytheon Certified Architect applying strategic business architecture methods in the defense industry. His career has spanned physics research, engineering for the Navy and Raytheon, and multiple publications in the application of architecture to business strategy.

Stephen Marshall – Strategy Consultant, IBM

Stephen Marshall is a Certified Business Architect® (CBA®) with the Business Architecture Guild®, a Master Certified Architect with The Open Group, and a Senior Management Consultant with the IBM Institute for Business Value (IBV). He currently leads the IBV Global C-suite Study program in Asia-Pacific, co-authoring several pieces of thought leadership.

Acknowledgements

(Please note affiliations were current at the time of approval.)

The Open Group gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the following people in the development of this document:

- Chris Armstrong – Armstrong Process Group

- Mats Gejnevail – Combitech

- Sonia Gonzalez – The Open Group

- Harry Hendrickx – Hewlett Packard Enterprise

- Andrew Josey – The Open Group

- Gerard Peters – Capgemini

- Sarina Viljoen – Huawei

Referenced Documents

The following documents are referenced in this TOGAF® Series Guide.

- Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Michael E. Porter, Free Press, 1985

- The Future of Knowledge: Increasing Prosperity through Value Networks, Verna Allee, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003

- The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy, James Martin, American Management Association, 1995

- The Machine that Changed the World, James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos, Free Press, 1990

- TOGAF® Series Guide: Business Capabilities, Version 2 (G211), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/g211

The following documents provide useful background information:

- A Guide to Business Architecture Body of Knowledge® (BIZBOK® Guide), Business Architecture Guild®; refer to: www.businessarchitectureguild.org/page/About

- Open Business Architecture (O-BA) – Part I, The Open Group Preliminary Standard (P161), published by The Open Group, July 2016; available at: www.opengroup.org/library/p161

- The TOGAF® Standard, 10th Edition, a standard of The Open Group (C220), published by The Open Group, April 2022; refer to: www.opengroup.org/library/c220

1.1 What is “Value”?

The word “value” originates from the Old French valoir: ‘be worth’. It is the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something. Within the context of Business Architecture, it is important to think of value in the most general sense of usefulness, advantage, benefit, or desirability, rather than the relatively narrow accounting or financial perspective that defines value as being the material or monetary worth of something. Non-monetary examples of value in the business world include such things as the successful delivery of a requested product or service, resolving a client’s problem in a timely manner, or gaining access to up-to-date information in order to make better business decisions.

Value is fundamental to everything that an organization does. The primary reason that an organization exists is to provide value to one or more stakeholders. It is the foundation of a firm’s business model, which describes the rationale for how a business creates, delivers, and captures value. The Business or Enterprise Architect should be able to model, measure, and analyze the various ways that the enterprise achieves value for a given stakeholder. This includes the ability to decompose the creation, capture, and delivery of value into discrete stages of value-producing activities, each of which is enabled by the effective application of business capabilities (see the TOGAF® Series Guide to Business Capabilities). This Guide provides an approach and examples for modeling business value.

1.2 Approaches to Value Analysis

Several approaches have been used in the past to model, measure, and analyze business value. Three well-known (but often misunderstood) techniques include value chains, value networks, and lean value streams. Each approach has a distinct purpose and area of focus that positions it differently from the others – as well as from the value stream that is used within the context of Business Architecture, and which is the subject of this Guide. The value chain takes an economic value perspective; value networks are primarily concerned with identifying the participants involved in creating and delivering value; while lean value streams are all about optimizing business processes (primarily within a manufacturing context). Only the Business Architecture value stream is designed to create an end-to-end perspective of value from the customer’s (or stakeholder’s) perspective, and in doing so is more closely aligned to realizing an organization’s business model rather than the financial, organizational, or operational models that the other examples cater to.

Values chains, value networks, and lean value streams are explained and compared in detail in Appendix A.

1.3 Value Streams in Business Architecture

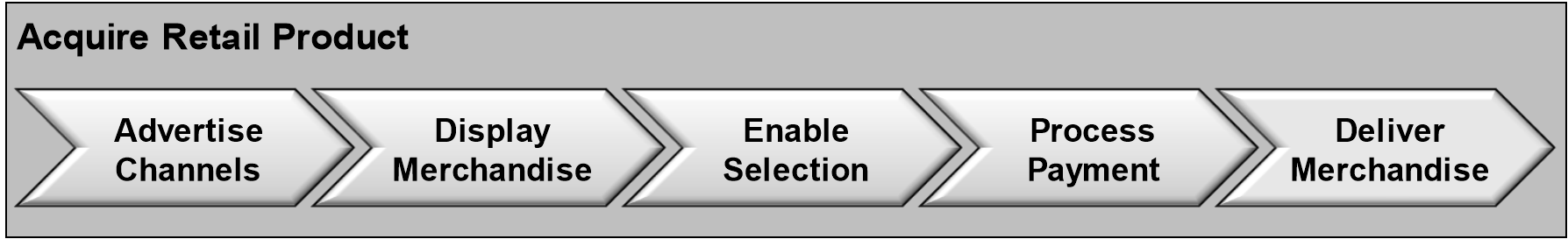

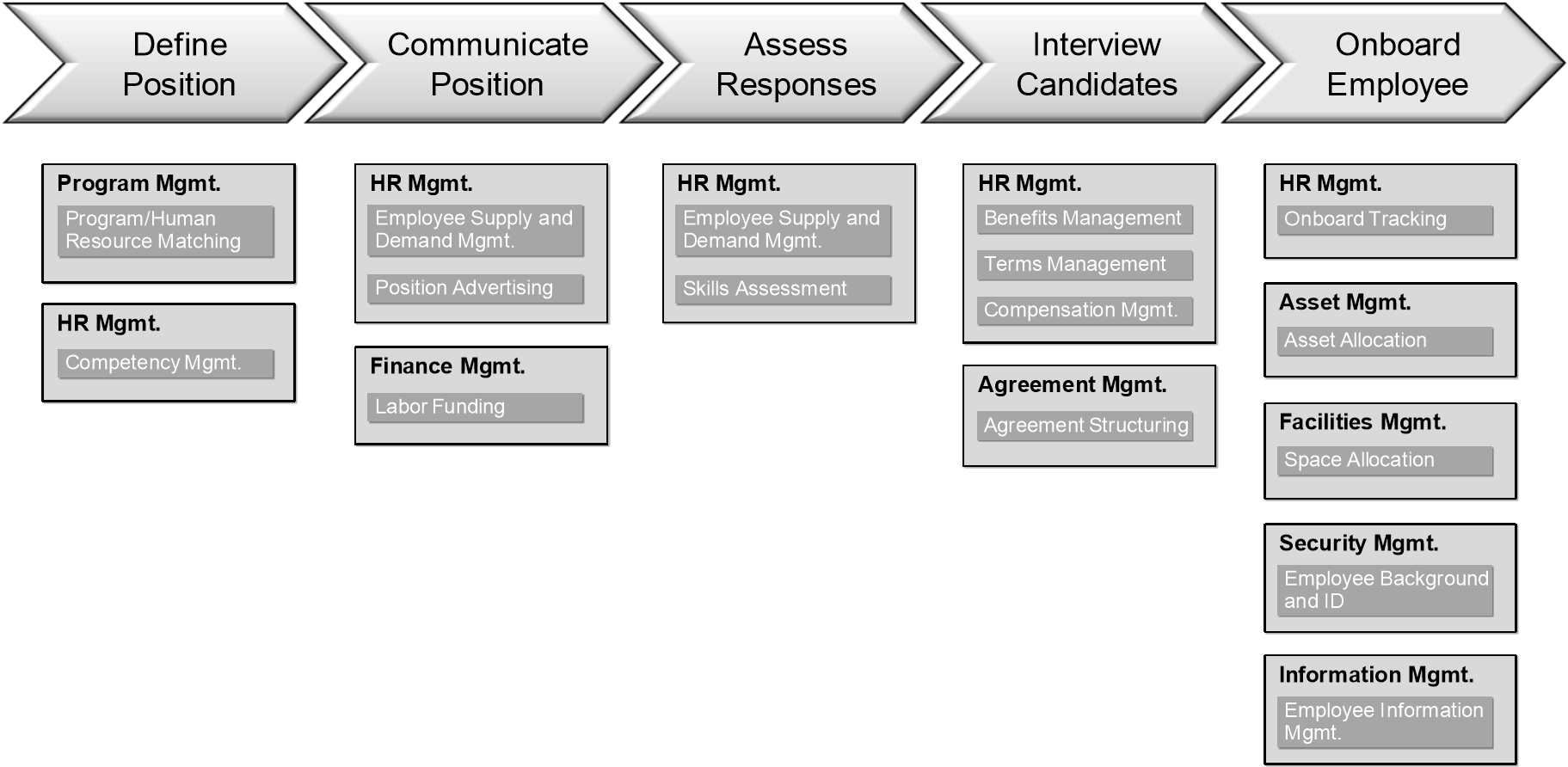

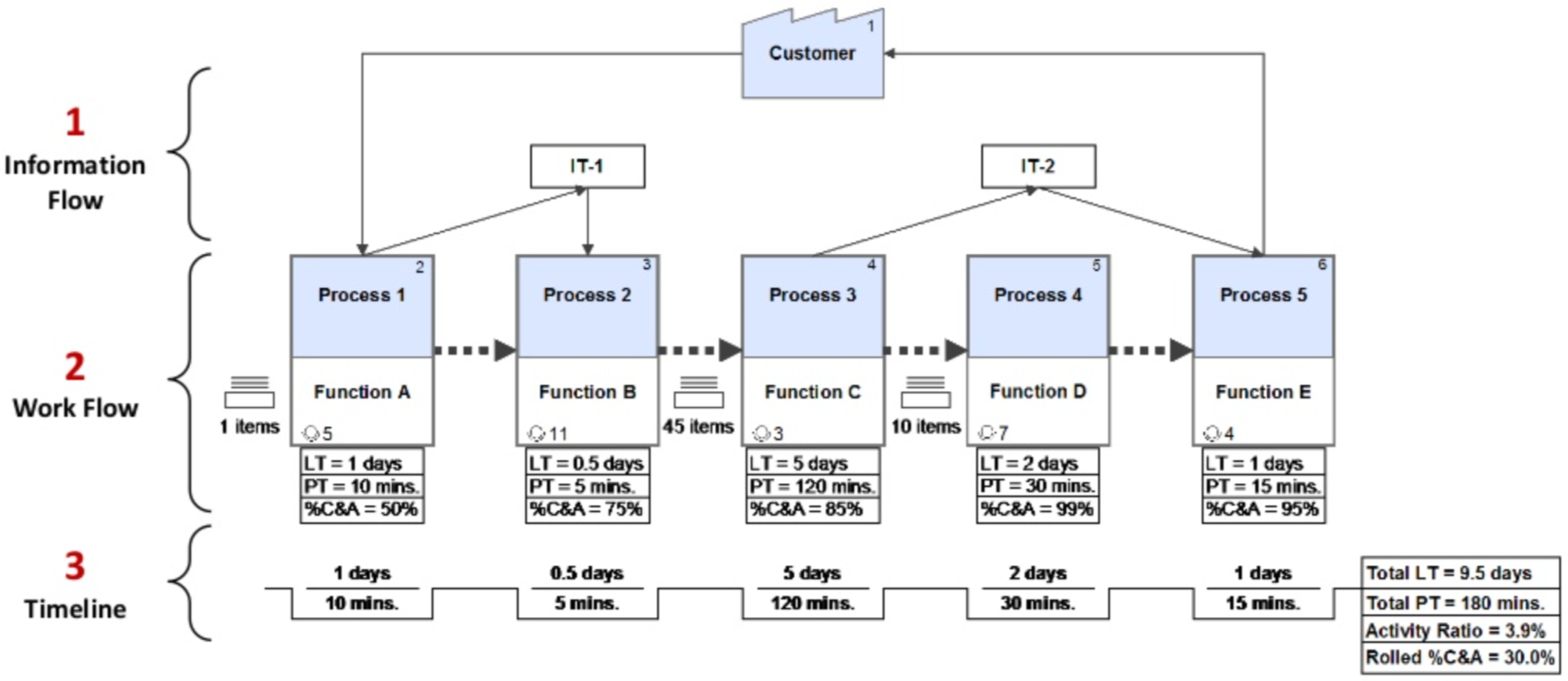

The approach to value analysis that is used in Business Architecture is derived from James Martin’s The Great Transition.[1] The value stream (a simple example of which is shown in Figure 1) is depicted as an end-to-end collection of value-adding activities that create an overall result for a customer, stakeholder, or end-user. In modeling terms, those value-adding activities are represented by value stream stages, each of which creates and adds incremental stakeholder value from one stage to the next.

Figure 1: Example of a Value Stream

Value streams may be externally triggered, such as a retail customer acquiring some merchandise, as shown in the example above. Value streams may also be internally triggered, such as a manager obtaining a new hire. Value streams may be defined at an enterprise level or at a business unit level. Either way, the complete set of value streams (as depicted in a value stream diagram or map) is simply the visual representation of all the value streams that denote an organization’s primary set of business activities. It is an aggregation of the multiple ways in which the enterprise creates value for its various stakeholders.

A key principle of value streams is that value is always defined from the perspective of the stakeholder – the customer, end-user, or recipient of the product, service, or deliverable produced by the work. The value obtained is in the eye of the beholder; it depends more on the stakeholder’s perception of the worth of the product, service, outcome, or deliverable than on its intrinsic value; i.e., the cost to produce.

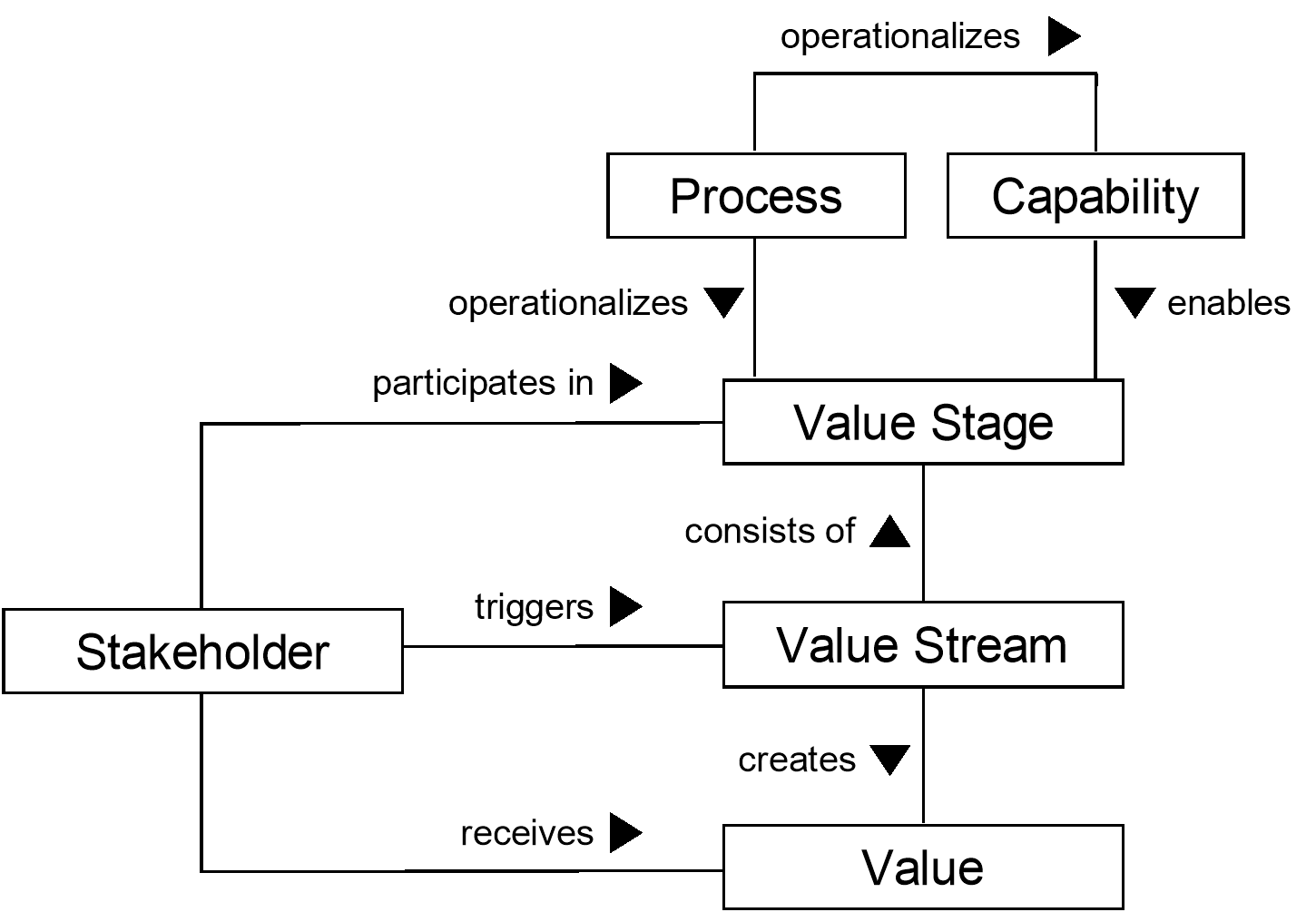

1.4 Relationship of Value Streams to Other Business Architecture Concepts

As part of the practice of Business Architecture, we separate the concern of what we do (business capability), from who does it (organization), from how value is achieved (value stream), from how it is implemented or performed at an operational level (process), from the information that is needed, from the systems that are used, and so on. Figure 2 shows the relationships between value, value streams, and value stream stages (discussed further in the next section), and other foundational Business Architecture concepts.

Figure 2: Value Stream Modeling Relationships

The complete set of value streams depicts the various ways in which an organization orchestrates its capabilities to create stakeholder value. The value stream has a direct linkage to an organization’s business model (specifically to the value proposition). As an organization translates its business model to an operating model, those value stream stages can be translated into business processes. Importantly, this translation (or mapping) is not a direct one-to-one type; a single value stream stage can map to one or more business processes. The process of mapping value stream stages to business processes is a reflection of operating model-level decisions about how to segregate a business model into the various different ways that an organization can structure itself.

Another way to think about the relationship between value streams and business processes is to consider their viewpoint: value streams take an outside-in perspective – usually a customer or end-user – and show how value gets created and moved around in relation to that stakeholder only. Business processes, on the other hand, tend to have more of an inward-looking, operational-level focus that is primarily concerned with how work gets done – the operational implementation. While some business processes may cover the same stream of activity that forms a value stream, it usually occurs at a much more granular level. That granularity is ideal for optimizing workflow and efficiency (i.e., incrementally improving existing activities), but it is far less suited to answering deeper questions about how a business should serve its customers in such a way that maximizes the value generated along the way.

1.5 Benefits of Value Streams and Value Stream Mapping

Mapping value streams (typically performed as part of a broader Business Architecture initiative) is a quick and easy way to obtain a snapshot of the entire business, since those value streams represent all the work that the business needs to perform – at least from a value-delivery perspective. Doing so helps business leaders assess their organization’s effectiveness at creating, capturing, and delivering value for different stakeholders.

Other benefits of value streams and value stream mapping include:

- Value streams help business leaders envision and prioritize the impact of strategic plans, manage internal and external stakeholder engagement, and deploy new business solutions

- Viewing business capabilities through the lens of a value stream provides a value-based, customer-centric context for business analysis and planning

- Value streams provide a framework for more effective business requirements analysis, case management, and solution design

- By focusing on how business value is achieved and for whom, a fully articulated value stream map can lead to more effective business and operating models that would not otherwise be identified using an inside-out or bottom-up design approach

This chapter describes the composition and structure of value streams, and the mechanics involved with breaking them down into value stream stages. It also explores the tight connection between value streams and business capabilities. Mapping value stream stages to their respective enabling business capabilities provides a much richer level of understanding about what a business should be focusing on (beyond the individual business capability map/model or value stream diagram).

2.1 Describing a Value Stream

While they are most commonly represented in diagrammatic form, value streams are defined using four standard elements:

- Name – The value stream name must be clearly understandable from the initiating stakeholder’s perspective. In contrast to the way that business capabilities are named, value streams use an active rather than passive tense. That usually means a verb-noun construct. For example, the two value streams that we use throughout this Guide are “Acquire Retail Product” and “Recruit Employee”.

- Description – While the value stream name should be self-explanatory, a short, precise description can provide additional clarity on the scope of activities that the value stream deals with.

- Stakeholder – The person or role that initiates or triggers the value stream.

- Value – The value (expressed in stakeholder terms) that the stakeholder expects to receive upon successful completion of the value stream. That value is an aggregation of the incremental value items that are delivered by each value stream stage.

Continuing with our earlier example:

|

Name |

Acquire Retail Product |

|

Description |

The activities involved in looking for, selecting, and obtaining a desired retail product. |

|

Stakeholder |

A retail shopper wishing to purchase a product. |

|

Value |

Customers are able to locate desired products and obtain them in a timely manner. |

2.2 Decomposing a Value Stream

Stakeholder value is rarely produced as the result of a single step or activity. More often, value is achieved through a series of sequential and/or parallel actions, or value stream stages, that incrementally create and add stakeholder value from one stage to the next.

Each value stream stage comprises the following elements:

- Name – Two to three words identifying what is (or will be) achieved by this stage.

- Description – A few sentences explaining the purpose and the activities performed during the value stream stage.

- Stakeholders – Actors who receive measurable value from the value stream stage, or who contribute to creating or delivering that value.

- Entrance Criteria – The starting condition or state change that either triggers the value stream stage or enables it to be activated.

- Exit Criteria – The end state condition that denotes the completion of the value stream stage; i.e., when the required value has been created or delivered to the stakeholders. This information becomes the entry criteria for the next value stream stage.

- Value Item – The incremental value that is created or delivered to the participating stakeholder(s) by the value stream stage.

A value stream does not necessarily flow continuously and uninterrupted from initiation through to conclusion. Following each value stream stage, there is an opportunity to stop the value stream if the desired value has not been created or delivered. This could be at the request of the participating stakeholder. For example, the Acquire Retail Product value stream may stop because the customer decides that they no longer want to purchase the merchandise after they see the price.

2.3 Mapping Capabilities to Value Stream Stages

Having defined the end-to-end value stream, the next step is to identify which business capabilities are required to enable each value stream stage. This is done by reviewing the business capability map, and linking (i.e., cross-mapping) the relevant business capabilities to each value stream stage (see the value stream to business capabilities mapping example in Section 4.2).

The purpose of this activity is to identify which business capabilities (out of the total set of capabilities) are critical to delivering stakeholder value, and therefore which ones need to be performed to a sufficient standard of quality to meet stakeholder expectations. It also helps to identify those business capabilities that do not contribute toward any of the core value streams, and which may be eliminated from the business.

A common question that confronts many Business Architects is which should come first: developing the value stream map or the business capability model? The short answer is that it does not matter, because one should not exist without the other for very long. Value streams provide valuable stakeholder context into why we need business capabilities, while business capabilities demonstrate what we need for a particular value stream to be successful.

In practice, it is often a lot faster and easier to draft a set of value streams than a fully-fledged business capability model. If you are starting from scratch, creating the value stream map first may be the preferred approach because you will be able to demonstrate results sooner, and the value stream map will help to inform the development of the business capability model.

3.1 Guiding Principles

- There must be a clearly defined triggering stakeholder – For example, the triggering stakeholder may be a customer initiating a discussion with a customer services agent.

- Start with external (usually customer-based) value streams – These value streams help to frame the range of possible internally focused value streams.

- Value streams are not capabilities, nor components of capabilities – Value streams and value stream stages help to inform and validate the business capability model, and vice versa. They specifically describe the sequence of activities that the business needs to undertake to produce or realize value. Whether the business can perform those activities to the level needed is a function of the set of business capabilities that it can call upon at each value stream stage.

- Keep it concise – Creating value streams and mapping them to business capabilities should not require going down to operational levels of detail. That is normally the domain of business process design. The operational level of detail can be derived from the value streams but that detail does not usually provide the overall, end-to-end perspective that is needed for strategy-level discussions and analysis.

4.1 Baseline Example

In this section, we apply the methods and framework outlined previously to a specific example, then put that example into action using business scenarios and heat maps.

We start with an external stakeholder value stream – the Acquire Retail Product value stream introduced in Figure 1. A more comprehensive scenario that includes heat-mapping and decision-making processes uses the Recruit Employee value stream that was first introduced in the TOGAF® Series Guide to Business Capabilities.

The first step is to define the value stream, as discussed in Section 2.1:

|

Name |

Acquire Retail Product |

|

Description |

The activities involved in looking for, selecting, and obtaining a desired retail product. |

|

Stakeholder |

A retail shopper wishing to purchase a product. |

|

Value |

Customers are able to locate desired products and obtain them in a timely manner. |

The second step involves decomposing the value stream into a sequence of value-creating stages. Table 1 lists the key elements of each value stream stage, including a description, the participating stakeholders, entry criteria, exit criteria, and the value delivered from each stage. This retail example deals with physical storefronts as well as online sites, so the terms used could apply to either channel or type of customer interaction.

Table 1: Acquire Retail Product Value Stream Stages

|

Value Stream Stage |

Description |

Participating Stakeholders |

Entrance Criteria |

Exit Criteria |

Value Items |

|

Advertise Channels |

The act of making customers aware of the company's products. |

Store or Website Owner |

Customer searches for product |

Customer selects channel |

Retail channel available to customer |

|

Display Merchandise |

The act of presenting products in a physical or searchable digital form. |

Store Employees |

Customer selects channel |

Customer views products |

Product options provided to customer |

|

Enable Selection |

The act of enabling filtering and assessments of the best product(s) matched to the customer’s needs. |

Store Employees |

Customer views products |

Customer selects product |

Desired product located |

|

Process Payment |

The act of taking and processing payment from the customer. |

Cashier |

Customer selects product |

Charges paid |

Delivery commitment |

|

Deliver Merchandise |

The act of getting the product into the customer's hands. |

Warehousing |

Charges paid |

Product delivered |

Product in user's possession |

4.2 Mapping Value Streams to Business Capabilities

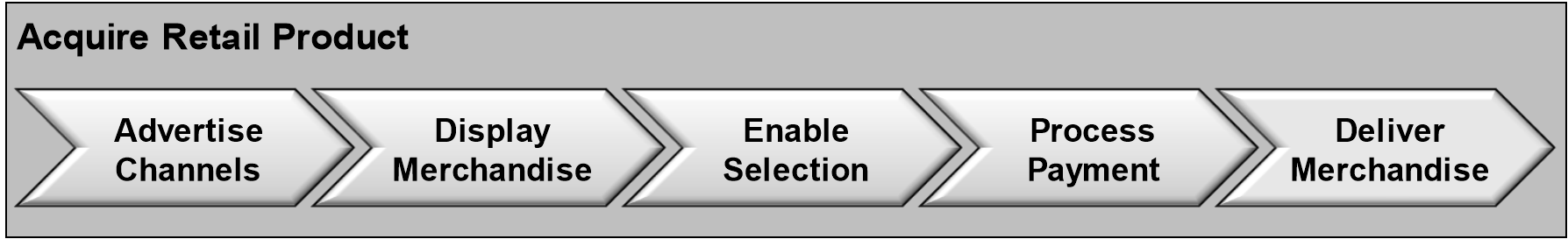

The second example focuses on creating internal business value via the activity of recruiting employees to join the business. It provides a more detailed example of mapping value stream stages to business capabilities and performing a gap analysis.

|

Name |

Recruit Employee |

|

Description |

The activities involved in identifying and hiring suitably qualified employees. |

|

Stakeholder |

A Hiring Manager looking to fill a specific position. |

|

Value |

A new employee with good fit for the job, hired rapidly, and working productively. |

How would a business determine whether this was an important value stream, worth the effort to model and apply to business decisions? It may result from a specific need or pain point that the business is currently suffering such as inefficiencies associated with disparate activities related to recruitment, or it may be part of a strategic assessment at an enterprise level to identify and document all of the core value streams for the company.

Once the need to model a value stream has been identified, pull together the right business stakeholders and subject matter experts to map out a draft value stream. Identify the major activities or stages that deliver chunks of business value, but without specifying the underlying processes, roles, information, or technologies that are required to execute that stage. The value stream diagram describes the value stream stages that generate the desired business impact, independent of the business capabilities required to perform it or assessments on whether it is performing optimally in the current state.

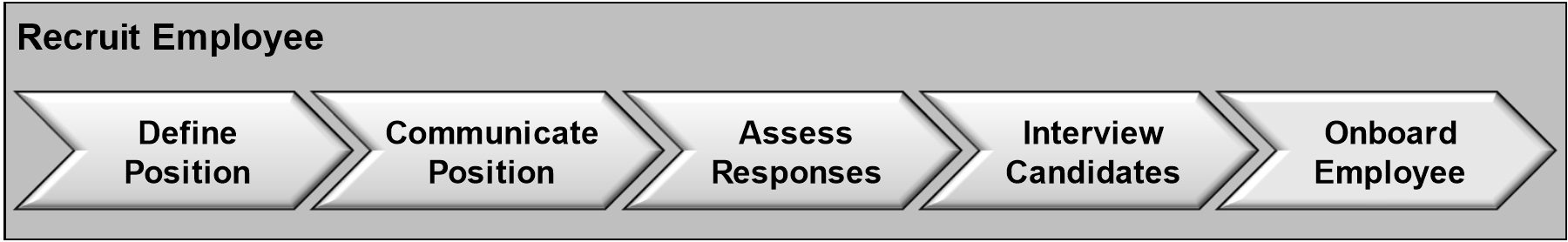

This first round of modeling may expose the fact that key experts who can cover the full, end-to-end value stream are missing from the room, so the modeling process will have to be done iteratively. As further refinement and alignment is achieved (usually with guidance from the Business Architect to ensure adherence to proven principles and rules), a value stream diagram such as the example shown in Figure 3 emerges:

Figure 3: Recruit Employee Value Stream

The next iteration involves the same experts developing clear definitions for each value stream stage, identifying the participating stakeholder(s) for each, and the value delivered at each stage (as shown in Table 2).

Table 2: Recruit Employee Value Stream Stages

|

Value Stream Stage |

Description |

Participating Stakeholders |

Entrance Criteria |

Exit Criteria |

Value Items |

|

Define Position |

The act of determining the need for staffing, identifying skills and qualifications, and documenting them. |

Hiring Manager |

Staffing changes identified |

Recruitment needs identified |

Time and expense saved on search for candidates |

|

Communicate Position |

The act of advertising, posting, or sending requisition information to available portals and recruitment events. |

Recruiter |

Recruitment needs identified |

Positions communi-cated |

High likelihood of finding qualified candidates |

|

Assess Responses |

The act of receiving, logging, distributing, and scoring candidate responses and additional checks. |

Hiring Manager |

Positions communi-cated |

Qualified responses selected |

Efficient use of interview time and costs |

|

Interview Candidates |

The act of communicating with candidates, arranging transport, and scheduling and conducting interviews. |

Hiring Manager |

Qualified responses selected |

Hiring decision |

Selection of the best employee |

|

Onboard Employee |

The act of making an offer, then triggering the embedded value stream for all activities involved in integrating the employee into the work environment. |

Employee |

Hiring decision |

Employee onboarded |

Productive workforce, meeting business commitments |

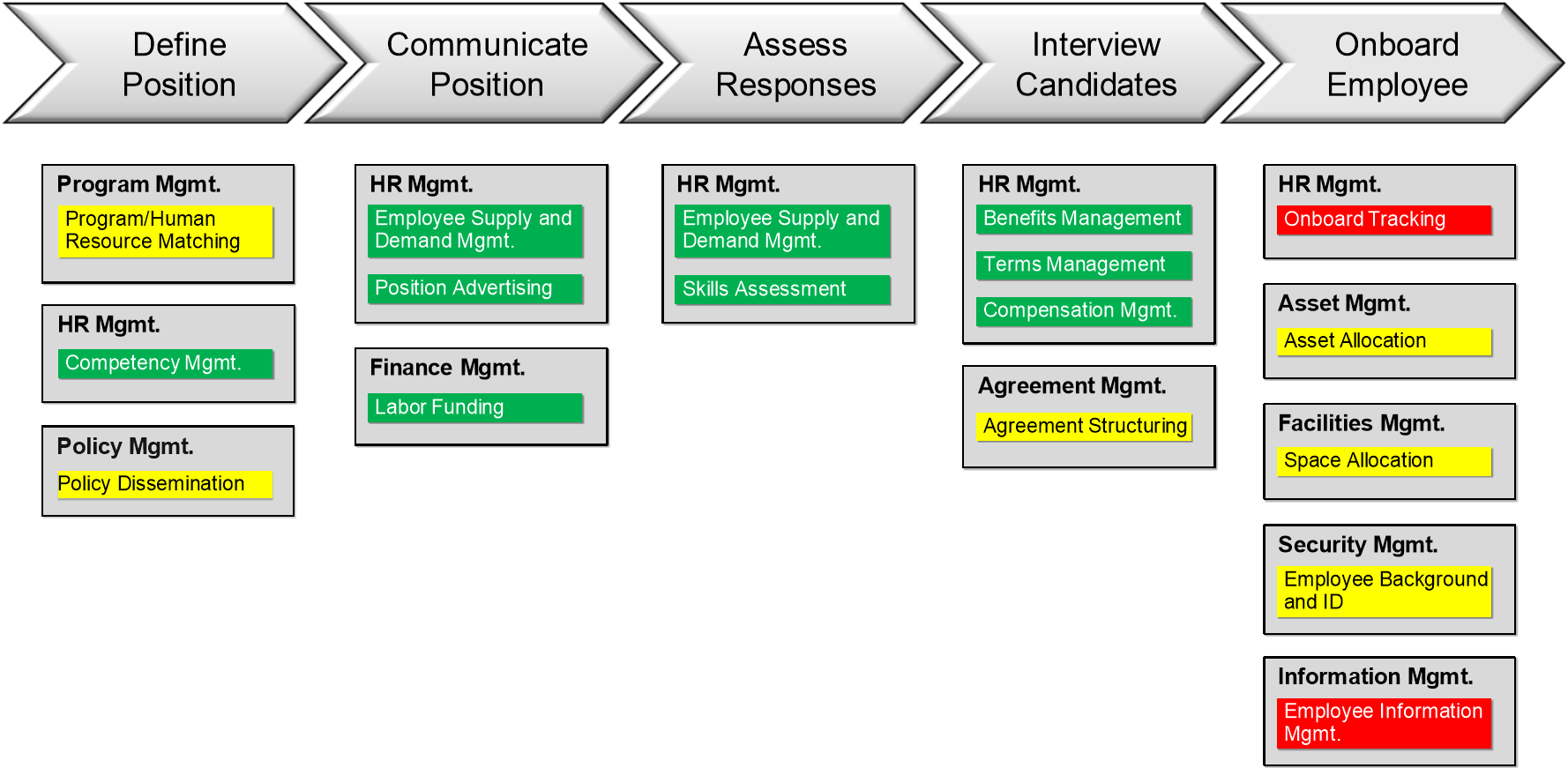

Finally, the group of experts (guided by the Business Architect) uses the company’s business capability model to map the enabling business capabilities to each value stream stage. The process involves focusing on each stage (in order), and then selecting the business capabilities that are most critical to enabling that stage. The level of detail, or how far down to go in the capability hierarchy, is driven by clarity on the specific capabilities in the company that contribute directly to supporting that stage and business value.

If every level 2 capability within a level 1 (parent) capability has a direct role in enabling that stage, then the mapping only needs to show the level 1 entry. For example, under the Interview Candidates value stream stage, if the level 2 child capabilities under HR Management comprise the complete set, then showing the level 1 capability is sufficient. As shown in Figure 4, if only certain level 2 capabilities are included (or even lower levels), then each of those lower levels needs to be shown explicitly.

Figure 4: Cross-Mapping Value Stream Stages to Business Capabilities

Note that most of these business capabilities are supporting capabilities, in the nomenclature of the three tiers introduced in the TOGAF® Series Guide to Business Capabilities. They focus on the ability to manage key functions inside the business (in contrast to market customer-facing capabilities or strategic planning capabilities). Value streams relating to products or services sold by the business (such as the Acquire Retail Product value stream used in the earlier example) will typically map to more capabilities in the other tiers.

4.3 Heat Mapping Scenario

Our fictional company has been hiring in response to growing market demand. The acceptance rate has been trending down, and the buzz on social media suggests that the company has not been treating new employees well. HR initiates a business capability and value stream analysis to determine how that could be happening.

The Recruitment Director assembles a cross-functional team including Program Management, Finance, Asset Management, and the company’s lead Business Architect. The Business Architect takes the team through the Recruit Employee value stream and helps them to refine it to better represent their company’s approach in the future. The Business Architect also guides the team in mapping their business capabilities to the value stream stages of the target or future-state value stream, resulting in the value stream-to-capability cross-mapping shown in Figure 4.

Next, the Recruitment Director provides a description of the problem, specifically the growing issue with employee acceptance rates. Using the subject matter expertise within the room, the Business Architect looks at how well each business capability supports the required value to be delivered from the respective value stream stage (looking vertically up the value stream map), with a focus on the issues around offer acceptance. This results in an initial heat map showing a couple of reds (significant gaps between what is needed to deliver business value and how it works today) and a few yellows (some shifts needed). The Program Manager is insistent that the biggest problem lies in how long it takes to provide new employees with a computer, network access, and mobile devices, but the HR Director and Business Architect suspect that the issue isn’t that simple and recommend using the heat map as a focus for gathering more detailed information about each of the gap areas before reaching a conclusion.

A week later, the team reconvenes with more information in hand. As each representative relays their findings along with a deeper understanding of cause and effect, a key theme emerges. It turns out that an employee in IT, who retired four months back, used to manually track the onboarding sequence from start date through orientation, security processing and identification, office space allocation, asset provisioning, and turning on network and system access for the employee. IT had assigned a person to perform that task because a lack of computing assets had been called out as a critical failure in the past. The root cause was the lack of a role to track the whole onboarding sequence. Since this person retired and nobody else had taken on the role, new employees had been experiencing much longer delays from onboarding to reach full productivity.

The team updated the heat map to that shown in Figure 5, making two critical changes. First, the team recognized that Policy Dissemination was a key capability enabling this value stream, and added it to the first value stream stage. Second, the gaps were recognized as driving a need for a new subordinate value stream to recognize the broad set of functions, systems, and roles touching employee onboarding, with the subsequent need for a value stream owner to improve company recruitment.

Figure 5: Heat Map for the Recruit Employee Value Stream

The use of value streams is an important Business Architecture technique, designed to understand what value needs to be created and delivered to each group of key stakeholders in order for it to be successful. Decomposing value streams into value stream stages provides a clearer understanding of how that value is (or needs to be) created or delivered, as well as what business capabilities are necessary to support those critical value-adding activities.

Value streams and value stream maps are, in effect, the counterpoint to business capabilities and capability maps. Whereas business capabilities deal with what a business does, value streams focus on the actions describing (at a high level) how a business delivers value to its stakeholders – through the effective combination of those capabilities. Value streams thus have an intrinsic relationship with business capabilities. Together, they form a powerful analytical device with which to unpick the constituent parts of a business to better understand its inner workings, to assess the degree of alignment between the organization’s mission and the activities it performs in support of that, and to identify where opportunities for improvement exist.

In this Guide we have shown that mapping value streams provides a powerful way to obtain a snapshot of the entire business in conjunction with business capabilities, since those value streams represent all of the work the business needs to perform from a value-delivery perspective. Doing so helps business leaders assess their organization’s effectiveness at creating, capturing, and delivering value for different stakeholders. The methods and examples provide a starting toolset for the architect to model the most critical paths for a company to deliver business value and enable business strategy.

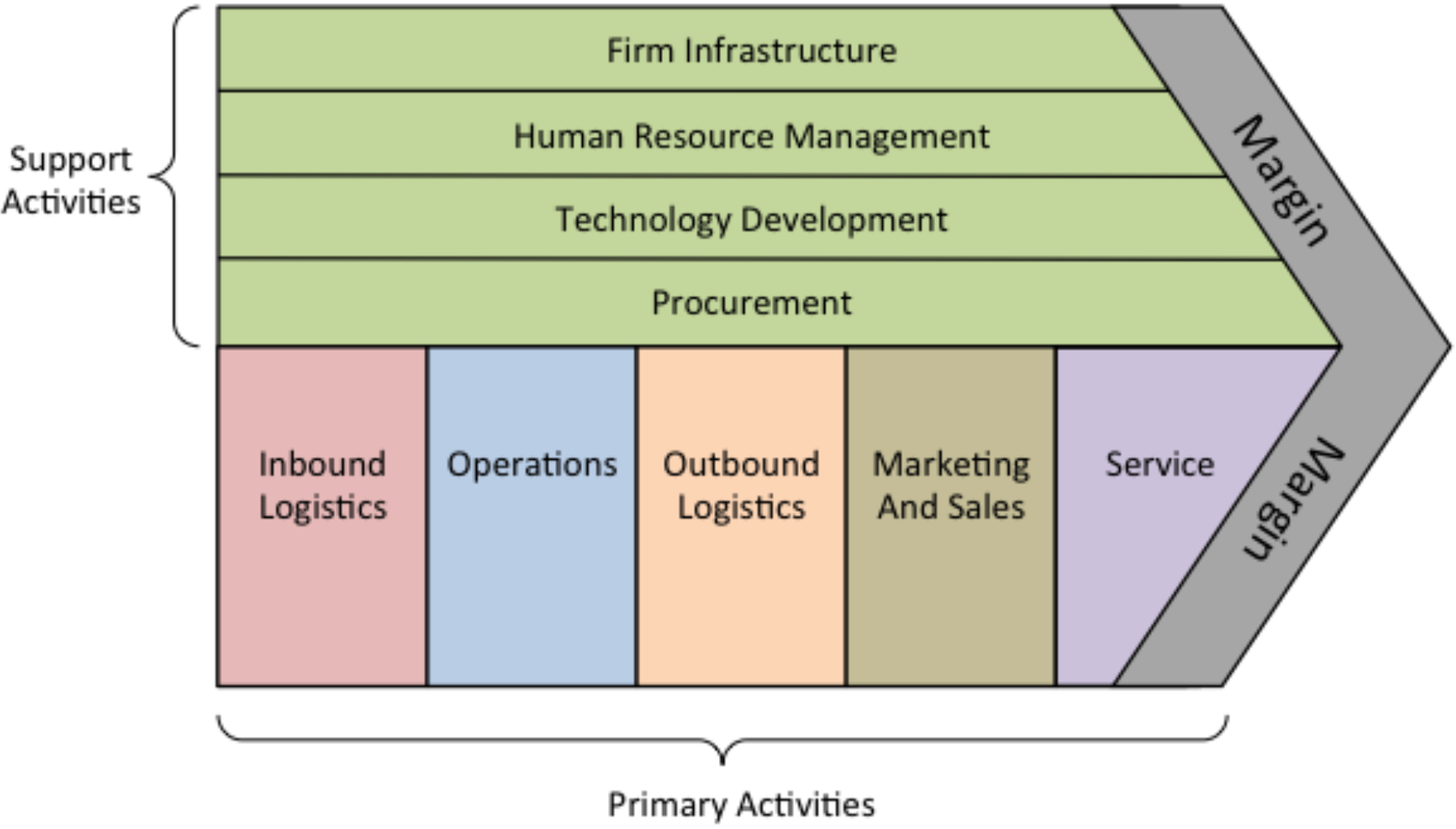

A.1 Value Chain

Value chains were introduced by Michael Porter in his book Competitive Advantage:[2]

“The value chain disaggregates a firm into its strategically-relevant activities in order to understand the behavior of costs and the existing potential sources of (competitive) differentiation.”

With its primary focus on activity costs and margins, the value chain perspective is mainly concerned with understanding how economic value is created. However, value chains (an example of which is shown in Figure 6) lack a structure from which to model, decompose, and analyze how a business combines its various capabilities to produce useful outcomes for stakeholders – which is the raison d'être of the value stream. In other words, value chains provide a macro-level view of how a business produces economic value (i.e., money), whereas value streams provide Business and Enterprise Architects the opportunity to decompose the end-to-end value producing system into sequences of core activities enabled by business capabilities.

Figure 6: Michael Porter’s Value Chain

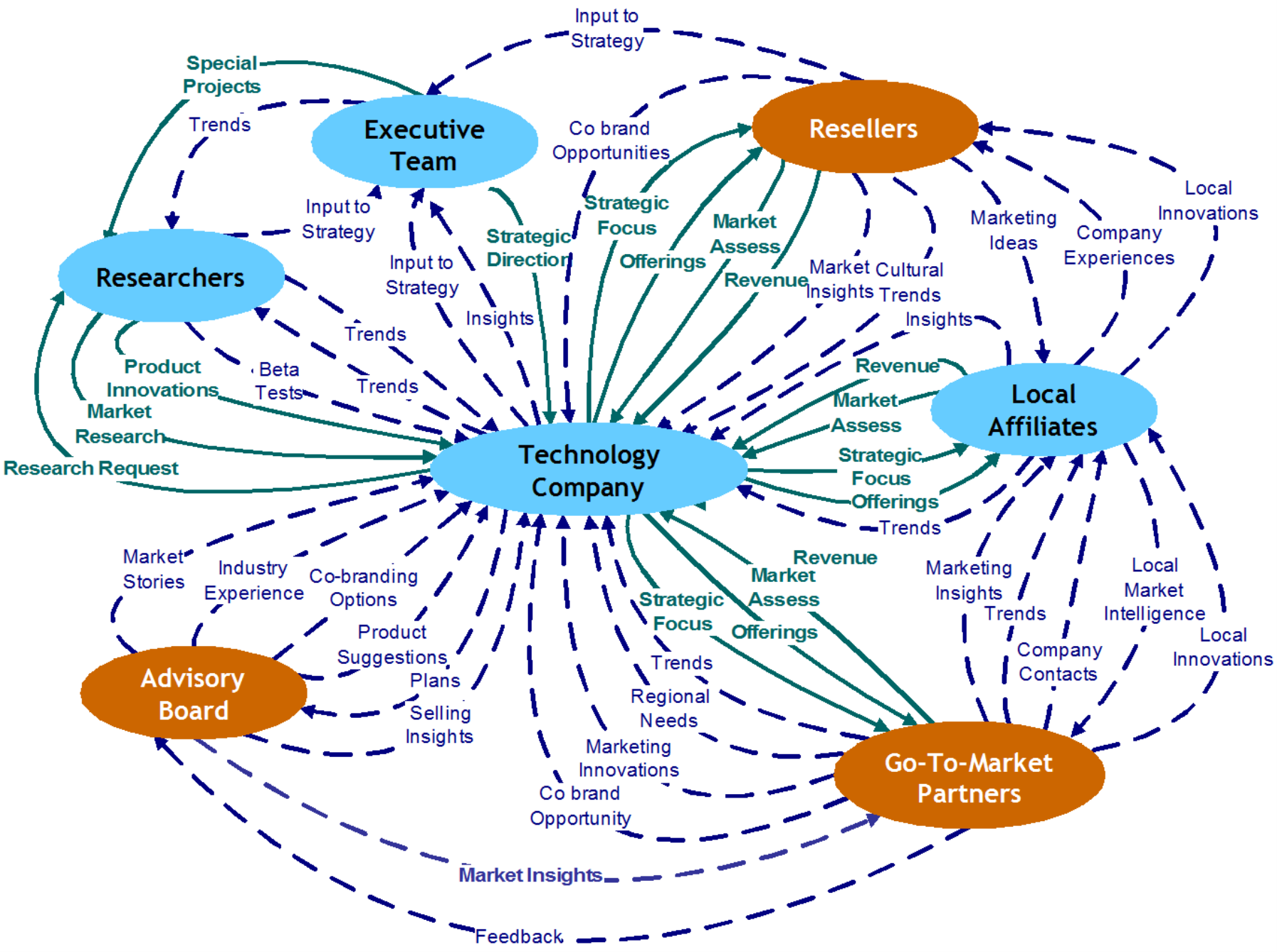

A.2 Value Network

Value networks[3] are focused on describing the social and technical resources that exist within and between businesses. As shown in Figure 7, the nodes in a value network represent people, or roles, in an enterprise. The nodes are connected by interactions, which represent deliverables that might be tangible (products or cash) or intangible; e.g., increased knowledge.

While value networks deal with the same sort of elements as value chains, the main difference is to do with intent: the primary purpose for creating a value network is to understand the complex web of relationships and areas of value exchange that exist within and between businesses.

A.3 Lean Value Stream

Lean value streams came out of the Lean Thinking movement,[4] which originated in the automotive industry in Japan (at Toyota, the process is known as “material and information flow mapping”). The core premise of Lean Thinking is to identify and eliminate waste from a firm’s processes, with the goal of only retaining those activities that create or increase value for the end-user. The lean value stream is a diagrammatic representation of the sequence of activities required to design, produce, and deliver a good or service to a customer (see Figure 8). By adding performance metrics around each process (such as Processing Time, Response Time, and Percent Complete & Accurate), it becomes possible to use lean value streams to identify opportunities for waste reduction.

Despite the similarity in name to the Business Architecture value stream, the lean value stream’s primary purpose is to document, analyze, and improve the flow of information or materials required to produce a product or service for a customer. It is not designed (nor is it well suited) to broader architectural purposes – namely, decomposing down to the critical activities (or stages) that progressively combine to produce value for a stakeholder, or cross-mapping those value stream stages to the enabling business capabilities.

Footnotes

[1] See the referenced The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy, by James Martin.

[2] See the referenced Competitive Advantage, by Michael Porter.

[3] See the referenced The Future of Knowledge, by Verna Allee.

[4] See the referenced The Machine that Changed the World, by James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos.

return to top of page

return to top of page