4 Enterprise Context and EA Context

To develop an EA Capability requires an understanding of the enterprise in question. The understanding gained through this exercise is the foundation for tailoring, prioritizing, and building an EA Capability. The focus of this chapter is to gain an understanding of the context and the need for an EA Capability to be built for the enterprise.

Every enterprise has a different context – the circumstances that led to its creation and current setting must be fully understood and assessed. Without an explicit understanding of an enterprise’s context, there is a risk of carrying an implicit or derived context into the analysis, usually based upon prior experience or an enterprise’s recent past. Proceeding with derived context often results in failure of the EA Capability. Creation of an EA Capability is often associated with change events, and must be aligned with the current context.

Questions that must be answered to have clarity about the enterprise context and an EA context include:

- What is the enterprise?

- What is the enterprise’s purpose or mission?

- What is the enterprise’s strategic position and approach?

- What is the enterprise’s environment?

- What is the special context of the EA Capability?

- What architecture principles will drive choices?

Strategic business architecture involves understanding what the enterprise is, analyzing the purpose for the enterprise and success measures, along with its environment. Operational business architecture is about analyzing, documenting, and refining how the parts of the enterprise execute their work on a day-to-day basis.

Providing context requires strategic business architecture. Developing other capabilities uses the same understanding. Developing these descriptions is iterative. This chapter will describe why it must be iterative. The first principle of being iterative is to obtain the level of detail necessary to answer the question at hand, and, as the questions become more precise, to increase the level of detail captured.

Always revisit existing material to simply confirm that the content is current. Refine or update only when necessary. When existing principles are available, review the existing architecture principles to understand how the EA Capability has been framed regarding purpose, role, and engagement. It is too early in the process to start creating principles.

4.1 What is the Enterprise and What is its Purpose?

The very first activity is to define the enterprise. The term is defined as “the highest level of description of an organization used to identify the boundary encompassed by the EA and EA Capability”. In practice, the enterprise is a boundary that identifies the outer limit that the EA and the EA Capability must address. In some cases the boundary will align with a corporation; it can align with an extended enterprise, including business partners in an organization’s value chain; it can align with a set of organizations joined by a common mission, such as a multi-national peacekeeping force; lastly it can limit the boundary to part of an organization. The term is used flexibly to identify the boundary of the EA and remit of the EA Capability. The size of the enterprise is not a consideration.

What is included and excluded from the boundary of the enterprise impacts every aspect of an EA Capability. The Leader must ensure that the EA Capability addresses the complete scope of what is included the enterprise, and all related governance.

The second is to understand the enterprise’s purpose. Private, public, or social enterprises will have distinct purposes. Private enterprises exist to generate value for their shareholders. The purpose will be drawn from the product and service they provide, and the industry segment in which they operate. Mission, or vision, statements will typically describe a purpose. Public and social enterprises typically have a purpose described in their mission or mandate.

Note: This Guide will operate on the assumption that the enterprise is a profit-making, public organization. This Guide also assumes that the EA Capability team is chartered to define the target architecture by the highest decision-making body (like the Board or the CEO), covering all departments, divisions, and geographies.

4.2 What is the Enterprise’s Strategic Position, Approach, and Environment?

Structuring the EA Capability requires an understanding of how the enterprise works. To play in the market context, the enterprise defines how it competes and serves customers in its market – also known as the strategic statement. Exploring the enterprise context and the strategic position is done by understanding the following:

- Business Model

- Operating Model

- Organization Model

- Econometric Model

- Accountability Model

- Risk Management Model

Even when a strategy statement is available, the spirit and intent can be better understood by exploring these models. Development of the strategy for the enterprise rests with the Executive Board, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), or the Chairman. The EA Capability team or its Leader may be asked to facilitate the strategy development session. The EA Capability Leader or the EA Capability team should not create or own the strategy statement of the enterprise. When an explicit strategy statement is not available, explore the models presented below to understand whether the enterprise is operating under implicit interpretation. When the strategy is not stated explicitly or implicitly, it is upon the EA Capability Leader to request the Executive Board, CEO, or the Chairman to define the strategy.

4.2.1 Business Model and Operating Model

The business model for an organization changes to stay current with the economy and environment within which it operates. Michael E. Porter, in his 1979 article titled How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy,[10] stressed the needs to track external and internal factors. As described by Alexander Osterwalder,[11] the business model can be extended to build a comprehensive model for complex enterprises – customers, beneficiaries, partners, suppliers, and regulators – as follows:

- Purpose of business and value proposition to customers, beneficiaries, partners, suppliers, and regulators

- Channels of engagement with customers, beneficiaries, partners, suppliers, and regulators

- Internal and external activities that add value to customers, beneficiaries, partners, suppliers, and the enterprise

- Partnership activities and details of sharing cost and revenue

- Revenue models, including benefit realization streams

- Cost structures and their mapping to internal and external activities

- Planning cycle (when the investments will be made) and impact delivery cycle (who will realize what value and benefit at what point in time in the future)

The business model is an indicator of the cash flow and cash reserve management approach of the enterprise, including how it plans to stay in business for a conceivable period in the future. The smaller the financial margins, the higher the need for operational efficiency capabilities – lean but effective architecture to sustain the business. A higher profit margin is one of the several factors that results in poor sponsorship for a dedicated EA function. There are other factors like compliance, governance and risk, and challenges with long-term planning that may instigate a need for EA Capability to be built. When the team providing the EA Capability is aligned to an organizational unit that is operating as a cost function, sponsorship for the EA Capability will not be dependent on the financial margins of the organizational unit.

Identify the business model for the enterprise “as-is” today or the direction for the next few years. Business models evolve with economic and social maturity. Alexander Osterwalder discussed how disruption to an industry or a business model can be caused by altering any one of these aspects. The business model drives the selection of the appropriate operating model. As the business model changes, the operating model will have to be adjusted. Over the past few decades, as the highly inter-dependent global economy emerged, the nature of external forces and their impact on the operating model evolved as well. Some of the key literature on these forces are (see also Appendix C):

- The Living Company, by Arie De Geus

- The Structuring of Organizations, by Henry Mintzberg

- The Delta Model, by Dean L. Wilde II and Arnoldo C. Hax

- The Core Competencies, by C.K. Prahalad, Allen Hammond, and Stuart L. Hart

- The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, by C.K. Prahalad and Stuart L. Hart

An operating model is the conceptual representation or a description of how the enterprise executes its broad functions to achieve its stated purpose. The rationale behind how the enterprise executes its functions to achieve the stated purpose is called a business model. A pivot for a business model is the ability to manage cash flow and profitability considering how it functions, whereas an operating model is just the description of how it functions.

For example, a philanthropic organization’s business model is about the activity to achieve a social goal – like availability of clean water to people hit by floods. Distinct business models would be aimed at raising funds to provide this service, put people in the field to directly deliver the social goal, or both. The operating model for this organization defines how awareness is maintained to raise money, how to respond to such needs, and to show results that the need is being met efficiently and effectively.

To get started with documenting business and operating models, consider the following pivots:

- Ownership of design of products and services, and how it is transferred to end-users

- How the products and services are charged (tactics to acquire customers)

- Diversity of products and channels employed

Operating models bridge the detailed organizational design with the strategy, values, and purpose of the enterprise. In simple terms, the operating model describes the internal expertise required and how the resources are managed to provide the services to customers of the enterprise.

There are several templates and references available for documenting the operating model – differentiated by industry or geography or by public, private, or social incorporation. It should be noted that some of the industry verticals (e.g., retail, wholesale, online, digital) have their own versions of operating model classification. The Center for Information Systems Research (CISR) model shown in Figure 3 is industry-neutral and focuses on patterns for how business processes are handled by the enterprise for growth and sustainability.

It is possible for the same firm to have more than one operating model. Common examples can be found in financial services or the Engineering, Procurement, Construction, and Management (EPCM) industry. A global banking and insurance company operating in, say, the United States, Brazil, and Germany may have a replication model – each country unit operates as its independent entity offering insurance and banking products and meets the needs of local demography and laws. Product design and financial structuring of these three units may replicate best practices of one another across each unit. The global holding company may be performing a coordination function to assure viability of the organization’s business model to its investors.

While capturing the operating model, it is essential to explore and document the value of products or services or both delivered by the enterprise, its target market, value chain, revenue generation model, and the strategic advantage of the enterprise. Another dimension to consider while creating the operating model is the core nature of the business such as a manufacturing, marketing, sales and distribution services, professional services, community business, or public utility core nature. Value chain and revenue generation models will be covered in detail later in this Guide.

Figure 3: Operating Model[12]

The best way to capture and validate the operating model is by stakeholder analysis.

4.2.2 Operating Environment and Compliance, Regulations, Industry Standards

It is normal that the law catches up with practices of organizations to assure common good for the mass population. As innovations happen, the enterprise tends to believe that is it not under any compliance or regulatory restrictions. Though not apparent, functions like HR and finance always fall under some form of regulatory controls.

Simple research on some legal issues faced by the new enterprises disrupting global taxi operations in 2015 is an illustration of the tension between innovation, social balance, and law. An enterprise that is making new armor to protect human life is probably inventing new material for which no standards exist for mass production or testability. Just like medicinal drug formulation, this enterprise is also required to follow a protocol for development and validation before entering the live human trial phase. It is one of the responsibilities of the EA Capability Leader to educate the executives and other Leaders in the enterprise, where standards and compliance apply and where the enterprise is a pioneer if they are not acknowledging these needs easily.

It is a good practice to create a catalog of compliance needs, local and international regulations, and industry standards that apply to the enterprise.

4.2.3 Organization Model of the Enterprise

In most cases, the enterprise should have an organization model, and it is good enough for the EA Capability team to have it accessible. In the event the EA Capability’s chartered scope is one business unit, product line, or geography, analysis discussed in the next few paragraphs should be limited to identifying dependencies and influences. Essentially, what the enterprise is must be defined in the context of what is being expected from the EA Capability effort.

An organization structure or organization model provides insights into leadership style, authority and center(s) of power, and values of the organization. It also informs lines of communication, local and global culture, segregation of duties, and resource allocations to achieve the stated mission and objectives of the enterprise. The model will provide insights into the kind of challenges the enterprise faces.

Note: The yellow icons represent the geographical locations from where the teams could be operating.

Depending on the nature of business, the enterprise may be procuring raw materials or augmenting its work force via independent agents, partners, vendors, or all of the above. The Leader will have to create a catalog of key contacts and their locations for each type of “extension” to the enterprise. The version of organization model which needs to be documented may look like Figure 4, but this model is not an absolute reference.

The default organization model should reflect the lines of business or business units. Some of the other aspects to capture are locations, proximity to customer and interaction, value of innovation and data sovereignty (can employee, customer, partner, or revenue data be shared across geo-political boundaries), suppliers, and partners.

Performing an analysis of the current organization model informs how the enterprise prefers to employ human resources. Variants include grouping by skill set, by outcome, by line of business, or some by outsourcing non-essential functions. Understanding the mix of expertise and experience levels enables identification of intellectual property the enterprise wants to protect. Such analysis can be done in subsequent iterations of understanding the organization model. Creating an extended view as shown in Figure 4 will enable development of alternate viable options for business architecture or cost structure management.

A functional organization essentially follows Porter’s value chain model: marketing, sales, order management, product design, manufacturing, customer support, finance, HR, working as separate vertical units, brought together by business processes and interface procedures. Utility service providers are likely to have this model.

A product-based organization is pivoted by specific product lines, and products may not overlap with each other. Common functions like HR, finance, and marketing may either be duplicated by each product line or segregated as common or shared functions of the enterprise. Each product line is likely to have its organization head, sales, order management, product design, and manufacturing functions. Governmental organizations or organizations like General Electric with diverse products are likely to follow this model.

Organizations that are heavy on project-based execution are likely to have a matrix structure – where functional skill set specialization and maturity are managed by separate Leaders and product and operational needs are championed by different sets of personnel. Each execution effort will require functional and product leaders to agree upon team size and composition to complete the task at hand.

With each iteration, understanding the organizational model, clarity will emerge about the stakeholders, decision-makers, implementers, and functions of each organization. In the first pass through of this discovery, analysis, and documentation process, insights will be directional and indicative. As the depth of understanding of the organization model increases, quality and quantity of data for organization and functions will improve exponentially. This knowledge will enable development of appropriate models and views.

4.2.4 Scope the Impacted Teams

- Identify the core – those who are most affected and achieve most value from the work

- Identify the softly associated elements – those who will see change to their capability and work with core units but are otherwise not directly affected

- Identify the extended enterprise – those units outside the scoped enterprise who will be affected in their EA

- Identify communities involved – those stakeholders who are outside the scoped enterprise, and will be affected by the outcome delivered by the EA Capability – grouped by communities of interest

- Identify governance involved – including legal frameworks and geographies

Planning horizons are discussed later, at which point this Guide will go into the details of how time impacts the depth and breadth of detailing.

The level of detail regarding motivations, goals, success measures, and operational elements like toolset, inventory, data catalog, and solution provider should be scoped to meet the purpose of the EA Capability (Strategy, Portfolio, Projects, or Solution Delivery), and the planning horizon.

If it is decided to follow the Balanced Scorecard method, it is preferable to have the financial perspective defined for the whole enterprise, although a customer perspective may differ by segment; i.e., it can carry some of the common goals for all segments. Process and learning/development perspectives should be specific to the departments or divisions with common objectives for people maturity.

As this Guide discusses the team delivering the EA Capability, it will deal with opportunities to pursue multiple capability architectures at the same time. As the transformation is executed via projects or programs, seams and glue within the enterprise will present themselves and parameters for trade-off decisions will be solidified. The process naturally becomes replicable and scalable.

4.2.5 Econometric Model

Econometrics provides empirical models to economic relations, applying observational and experimental methods. One of the areas of econometrics involves arriving at the right price for the products and services offered by the enterprise. For this Guide, discussions are limited to documenting how the enterprise defines economic value and cost of mitigating risks. Some of the sub-models that make up the econometric model include:

- Accounting Model: total cash accrued = sum of sources of income – sum of all expenses

- Forecasting Model: the estimation of future impact of current actions, with a given set of constrained variables or risks for income and expense

Some of the risks the company would be handling are interest rate fluctuations, currency exchange rate fluctuations, inflation, and cost of raw materials. For example, a leading low-cost airline in the US managed its operational cost by placing appropriate investments in future fuel cost.

- Planning and Allocation: what are the trade-off criteria applied by the enterprise to distribute its investments across the enterprise?

For example, an enterprise has identified that IT investments should not be more than 3.5% of the enterprise’s total operating expense to maintain its overall operational efficiency. This constraint forces a trade-off between strategic and operational IT investments.

When it comes to operational expenses and building awareness around optimizations, models like chargeback and showback can be used as needed. For example, a leading IT service management vendor suggests using a showback system as a necessary step in the path to adopting cloud services.

Therefore, from an accounting perspective, the EA Capability team should be aware of:

- Ownership of the company – privately held versus publicly owned

- For-profit, not-for-profit, or governmental accounting principles

- Sources of funds for the enterprise or the team that the EA effort is impacting

- Controls for spending the funds – for the enterprise, the impacted team, and the EA Capability team

- How the spending on EA is accounted for in Operating Expenditure (OPEX), cost of product development, and the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

Some of the other dimensions to document are how the enterprise generates revenue and profit. A few generic models are:

- Creating products using intellectual property, including leveraging others’ products and services

For example, a paint manufacturer is creating a new product but uses machinery and products created by others. The formula for the paint is its intellectual property

- Buying, stocking, and reselling products made by other enterprises

For example, a distributor sources paint and painting supplies in bulk and then distributes them to smaller businesses.

- Offering management, financial, legal, technical, or support services with thorough understanding of other organizations or industries

For example, business services organization providing logistics consulting and implementation projects.

There are other ways to look at the revenue model based on how the enterprise views itself – like commerce and retail, subscriptions and usage fees, licensing, auctions and bids, advertising, data, transactions, intermediation, and freemium. These views are variations of the first three models.

It is possible that the enterprise may handle more than one such revenue generation model. Internally, any single division never has more than one revenue model. However, it is possible for one division to generate revenue from its intellectual property while other divisions may generate revenue by offering services in technology, general management, or project management domains. In such scenarios, understanding and separating by operating models will help define the right boundaries for the enterprise impacted by the EA Capability.

Investment priorities and spending patterns for the EA Capability will depend on the appropriate revenue and accounting model of the sponsoring unit of the enterprise. As the recommendations are turned into projects or operational efforts, the business and economic model of the enterprise will play a huge part in prioritization and rollout. This Guide provides detailed insights while discussing the governance model and process model for the EA Capability.

4.2.6 Accountability Model and Decision Model

An accountability model provides a balance between the sponsorship for the EA Capability and the expectations set for the EA Capability. This understanding is key to performing trade-off decisions across the stakeholder community. For example, when a change is made in the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), and an expected date for compliance is set, the decision to adopt the change either on the expected date or earlier is jointly decided by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and Legal Counsel for the enterprise. Likewise, the decision to upgrade recommended security software on a specific machine is best decided jointly by the data center administrator and personnel from the information security team. The EA Capability team normally operates in between the layers mentioned in these examples.

There is detailed management literature and research on this subject. Every enterprise has an accountability model and decision model, and a pattern to exercise this model.

The existence of these models is often not apparent to those who are not observant. The key focus is to understand the empowerment, freedom, political, and financial support provided to different stakeholders, the Leader, and the EA Capability to navigate competing priorities.

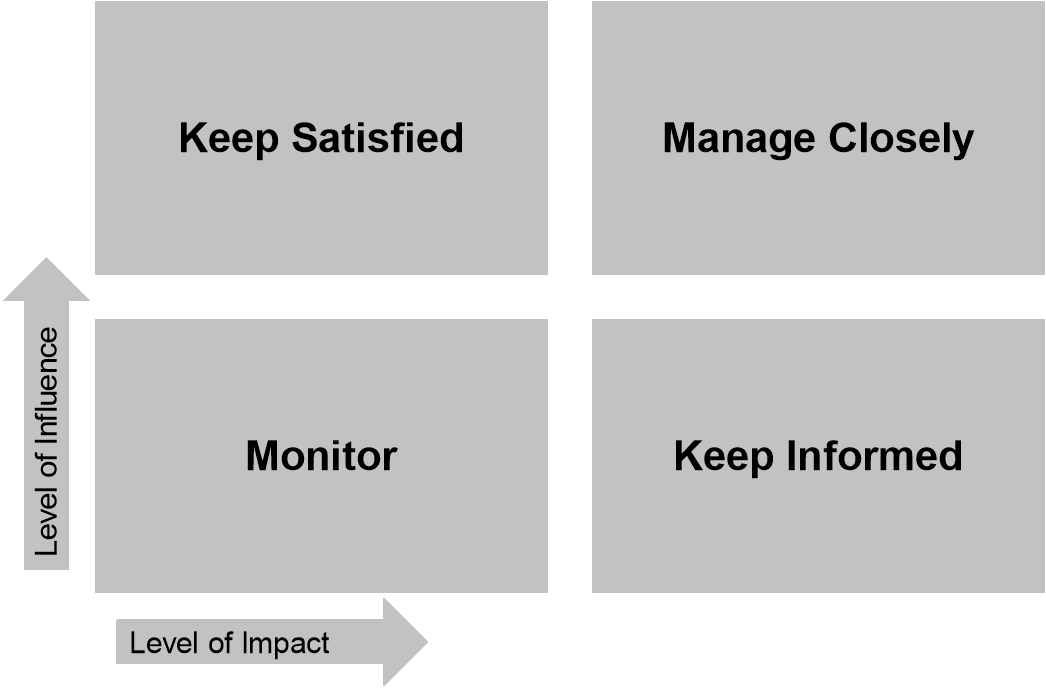

Depending upon the inclination of the enterprise, models like SCORE and RACI can be used to identify and document roles and accountability. The Project Management Institute (PMI) proposes a 2x2 matrix shown in Figure 5, which accounts for expectations, interests, the role in EA, and the role in the EA Capability for various members within the enterprise.

Documenting the accountability matrix reflects and informs key decision-makers on various business and architectural decisions. An effective approach is to ensure the role and accountability are identified to concerns, not the project. Different aspects of the project, or concerns, will have different accountability. It is important to define the organizational and decision-making boundaries, as the EA Capability will interact with various existing disciplines.

Figure 5: Project Management Institute Influence Matrix[13]

This may be the right time to consider who would be the right person to evaluate the effectiveness and impact provided by the EA Capability.

4.2.7 Risk Management Model

Central to best practice Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a very precise definition of the term risk. Within the risk management profession, risk is understood to be the: “effect that uncertainty has on the achievement of business objectives”. EA is one of the key tools that can be employed to:

- Support best practice ERM

- Reduce organizational risk

- Improve sustainability and profitability

Enterprises typically employ a formal or informal ERM framework to assess and manage risk at the enterprise level, increasing the visibility and transparency of risks to allow an enterprise’s management to make decisions on how to manage risk at an acceptable level for the enterprise. One of the essential steps to set up the EA Capability is to identify the risk management framework employed by the enterprise. The risk management model employed by the enterprise may not be apparent and might require some level of investigation.

From the EA point of view, there is a need to identify the risk appetite of the enterprise. Risk is a complex area, and central to an effective EA Capability. Consider an automobile insurance provider that is exposed to anti-theft technology introduced by auto manufacturers. While accepting this new technology, the enterprise may face a reduction in auto theft, hence lower cost of claims, or it may not work, leaving the current exposure level as-is. It may choose to perform additional anti-theft research, or employ data exchange with law enforcement and its competitors to validate and mitigate the unknown impacts. Find the pattern that is used.

For example, when the architecture roadmap includes adoption of a new technology or initiates a transformation effort is accepted for implementation, how does the enterprise approach and answer the following questions:

-

Using the Innovation Adoption Model shown in Figure 6, where does the enterprise fall in the bell curve?

It is possible that different parts of the enterprise may fall differently in this picture. It is essential to identify and catalog them.

- What is the deviation from projected costs that is considered acceptable?

(For example, 10% for the first year plan, 25% for the second and third years.)

- Which kinds and sizes of projects should go through additional layers of governance?

- If a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis is performed by the enterprise, what are the threat mitigation strategies and how are the efforts being quantified?

- Does the enterprise accept single-point failures such as vendor lock-in and interest rate variations?

- How often does the enterprise review the risks and effectiveness of mitigation efforts, and where in the enterprise are these addressed?

Figure 6: Everett Roger's Innovation Adoption Model (aka Technology Diffusion Model)[14]

If the ERM approach at the enterprise is not clear, it is important to initiate an effort to define one. The ISO 31000 Risk Management standard and The Open Group Guide: Integrating Risk and Security within a TOGAF® Enterprise Architecture, a guide specifically developed by The Open Group Security Forum in collaboration with The SABSA Institute (see Referenced Documents), are starting points to do so. Through this chapter, the Leader has been advised to look at the broad enterprise context. Within the enterprise, the EA Capability will be heavily influenced by the context created by the financial accounting model, planning horizon, and EA principles.

Understanding the enterprise’s purpose evokes key dimensions to consider. These agents specifically evoke the business rhythm and delivery schedule and value proposition guidelines for transformation efforts. They are critical agents to the design of the EA organization model and what kind of expectation the enterprise has for the EA Capability.

4.3 What is the Special Context for the EA Capability?

4.3.1 Financial Accounting Model

A Leader must identify and document the financial accounting model for the enterprise. The financial accounting model supports the business model and econometric model. There are two purposes to understanding the accounting model for the enterprise. The first is that it is the model that supports the economic purpose of the enterprise. Second, the accounting model helps to understand how the EA Capability is viewed – cost versus revenue function, Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) versus Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) versus Operating Expenditure (OPEX), or customer acquisition function versus operational efficiency (risk mitigation or capacity management) function.

Two major challenges for EA Leaders is to identify whether their work is considered as CAPEX and OPEX, and to find a way to balance the alignment of CAPEX and OPEX initiatives with the target architecture. The EA roadmap components will include both new building blocks as well as existing building blocks that have to be modified or decommissioned. The roadmap should include discrete steps to retrain, reallocate, or rehire resources for modification and decommissioning.

Some of the data points that can be derived from the accounting model are:

- An understanding of legal hierarchies – where credit-debit happens at the transactional level and where profits are accrued

- Silos and distribution of decision-makers and influencers

- Value measurement criteria for the EA Capability

- Investment amortization options while recommending projects

- Development of CAPEX versus OPEX, Return On Investment (ROI), Net Present Value (NPV), or Internal Rate of Return (IRR)-based trade-off guidelines

This list can keep growing depending on the enterprise’s design, approach, and the depth of understanding of the team providing the EA Capability.

Any enterprise is likely to have more than one financial accounting model, to suit the geopolitical conditions of each of the locations. Identify the model, understand it, and leverage PMO and finance teams to formulate appropriate business case and ROI models.

4.3.2 Strategic Planning Horizon

The planning horizon is the number of years into the future the enterprise will project its business and investment strategies. Different enterprises will operate substantially different planning horizons for the same level of planning. Knowing that the enterprise will look one, three, five, or ten years into the future for change programs, improvement initiatives, or capital planning will directly inform the structure and process integration of the EA Capability. Aligned to purpose, the EA Capability will have to provide inputs to align with the horizon.

Each enterprise has a different appetite for its planning horizon. Keep in mind that if most of the time spent by the EA Capability is on improving the immediate future, this impairs the ability of the EA Capability to deliver value. Consider carefully the purpose and effectiveness of the EA Capability when establishing a planning horizon.

The planning horizon and refresh cycle need to meet multiple scenarios, and fidelity demands of content provides an indication of release cadence for EA work and the workload for the team providing the EA Capability. This Guide discusses some of the strategies for evolving the EA Capability to balance the effort on the planning horizon in a later chapter.

4.3.3 EA Principles

Often EA Capability is not a greenfield effort. Most enterprises have undertaken the initiative to establish an EA Capability more than once. In the event the enterprise has a greenfield EA Capability, the Leader should revisit this chapter after having read Chapter 5 (Business Objectives for the EA Capability). Whether EA Capability is being set up afresh or reinstated or evolved, one of the enduring guidelines is a set of EA principles.

Existing EA principles provide a special context for prior activity performed by an EA Capability. It is important to review the existing principles for two reasons. First, they provide a context of previous efforts to establish a successful EA Capability – they inform how the EA Capability was viewed, viewed itself, and what purpose it was explicitly, or implicitly, supporting. Second, to ensure that they align to the actual enterprise context for the current EA initiative. This review provides insights on how the EA Capability has been framed regarding purpose, role, and engagement.

Review questions to ask include:

- Do the existing architecture principles represent the enterprise context?

- Do they represent all organizational elements of the enterprise such as domestic and overseas, primary, and supporting activities?

- Do they represent the preferences of the organization to which the EA Capability team is, or was, aligned?

Principles will balance the enterprise context and purpose of the enterprise. Care must be taken to ensure that the principles used to inform the development of EA and change projects align to the organizational context. Care must be taken to ensure that the principles used to inform architecture development align to the organizational context.

Where the existing architecture principles do not reflect the current enterprise context nor any organizational elements of the enterprise, additional work will have to be performed in the roadmap to establish the EA Capability. At a minimum, a new set of architecture principles will have to be developed. Further, existing target architecture, compliance assessments, and roadmaps should be revisited and assessed against the new architecture principles.

A primary function of an EA Capability is to improve understanding, simplify complexity, and improve informed, consistent decision-making. By extension, architectural principles should be tied to the enterprise’s values, goals, purpose, and strategies. These should inform, enable, and ground the enterprise on how to operate, transform, and grow. As a starting point, it is imperative that the team providing the EA Capability identifies and defines the situations when the consensus preference of the enterprise is to lean towards one trade-off. For example, the voice of the business outweighs the voice of the customer. Likewise, most decisions made in the context of EA are very difficult trade-off choices among two or more competing best, worst, or opposing options. A good set of architecture principles guides these choices and trade-offs.

EA principles should address the following purposes:

- Enable decision-making – it is important to set precedence during trade-off discussions and authority of tie-breaking if it must occur

- Align the enterprise – principles take subjectivity and bias out of the equation and drive critical conversations that are objective and aligned to the enterprise’s values

- Governance – how will the enterprise ensure that the right decisions are surfaced at the right time and with the right decision-makers, and, moreover, how to monitor the decisions and approach taken to arrive at the decision?

- Values and Culture – provide a better understanding about the enterprise’s culture and values; provide an approach and insight into how well the enterprise reacts to change

Keep in mind, anything the enterprise would perform during the normal course of business is not a principle. When the principle says “information is a valued asset”, it is important to test the opposite statement “when information is not treated as a valued asset, informed decisions, and progress cannot be made”, to validate whether the principle is valid.

TOGAF® is a registered trademark of The Open Group

return to top of page

return to top of page